Since 2019, Formula 1 has had a partnership with Amazon Web Services, giving it access to the Silicon Valley giant’s impressive array of cloud computing resources. The organization has leveraged this in a number of ways, such as race prediction information displayed on television feeds right through to development of the 2022 rule set (in conjunction with the FIA).

Professional Motorsport World speaks to Rob Smedley, former director of data systems at F1 and now a consulting engineer to the organization, to find out how the partnership gave F1 the capabilities to devise the most significant rules shake-up in a generation.

Showtime

The starting point for the new formula was ascertaining which elements of the previous car package were most detrimental to achieving closer racing. “If you go right back to the crux of why we have done the 2022 car, it all stems from what the customer wants. That customer is our fan base, and the fan base was fairly clear in requesting that they wanted closer racing. They wanted more wheel-to-wheel action,” says Smedley. “They want to see more close racing, which does not necessarily mean overtakes. Overtaking is the cherry on the cake, if you like. We set about trying to understand how to do that.”

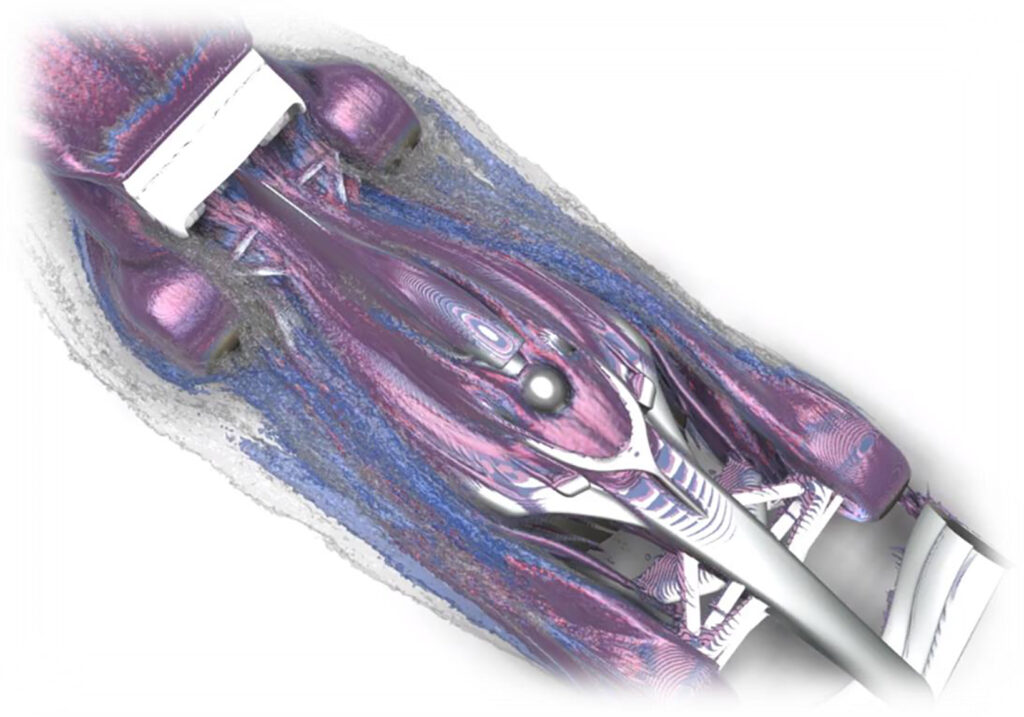

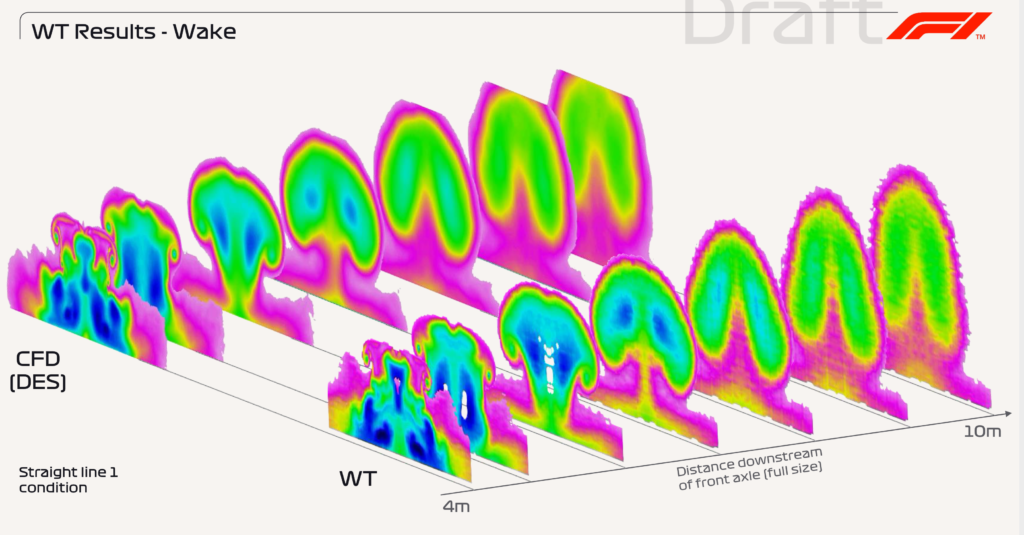

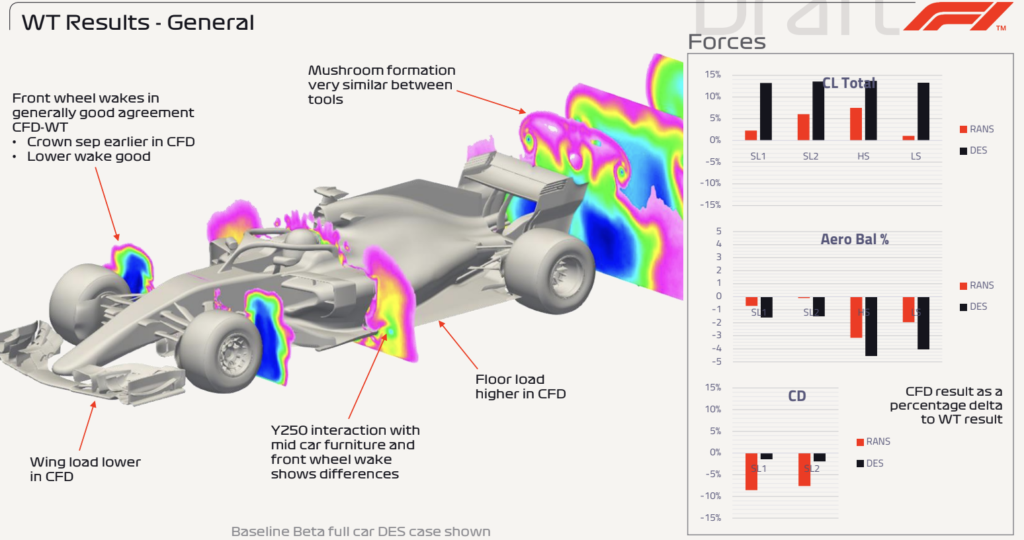

The process began by conducting an in-depth analysis of the aerodynamic behaviour of the then current cars when following each other. Starting in 2017 with an in-house team – including Pat Symonds, formerly of Benetton, Renault and Williams, and Nicholas Tombazis, formerly of Ferrari – F1 set out to make sure the regulations are not just guesswork. Key to this would be its acquisition of the wind tunnel model and CAD data for the Manor F1 team’s unraced 2017 car, which formed the basis for its research. Using these as a baseline, testing was undertaken in the Sauber wind tunnel in addition to CFD analysis to establish a reliable wake profile for the cars.

“We knew that turbulent flow structure that comes off the car in front is very detrimental for the car behind and we started to look into this in much more detail,” explains Smedley. “Our studies showed that when you get to say within half a second of the car in front, you start to really struggle with the turbulent air, and lose in the region of 40% of the downforce.”

“We knew that turbulent flow structure that comes off the car in front is very detrimental for the car behind and we started to look into this in much more detail,” explains Smedley. “Our studies showed that when you get to say within half a second of the car in front, you start to really struggle with the turbulent air, and lose in the region of 40% of the downforce.”

With this baseline established, F1 then set out to design a car that suffered less when following another car while also having a reduced wake. “That is where the first technology problem came in. Because what we did was, for the first time ever – well, not the first time ever, but the first time ever at scale – was develop a two-car model,” recalls Smedley.

Bring out the big guns

Bring out the big guns

A high-fidelity, two-car model requires a phenomenal level of computing power to solve in CFD; Smedley notes that using the resources permitted to teams under the current rules, each simulation run would take 40 hours to complete. Even though F1 was using the UK’s Archer supercomputer, Smedley admits, “That was in no way agile enough to be able to actually get through the amount of design work that we needed to get through.”

So it was that F1 approached Amazon as a technology partner and began to utilize its cloud computing resources. “We built a substructure within EC2 [Amazon’s Elastic Compute Cloud infrastructure] so that all of the calculations ran in the cloud,” says Smedley. “Doing that, we quadrupled the number of cores we were using as a baseline. That cut the runtime down from 40 hours to around seven.” The upshot was that the aerodynamicists working on the project could work through many more design iterations, as well as run concurrent simulation runs.

For Smedley, the computing firepower brought to bear was on a higher level than anything he had experienced before: “It’s mind-blowing the amount of power that we could call upon. At one point we had something like 14 concurrent jobs, running on 7,000 cores, with 2.4 billion cells of Navier-Stokes equations, all calculating concurrently!”

Working with the teams, who were permitted to undertake studies on particular areas of the 2022 rules outside of the rules-based restrictions, F1 went through a variety of vehicle design iterations until eventually settling on a basis for the new technical regulations, which were then codified into the FIA’s rules.

Working with the teams, who were permitted to undertake studies on particular areas of the 2022 rules outside of the rules-based restrictions, F1 went through a variety of vehicle design iterations until eventually settling on a basis for the new technical regulations, which were then codified into the FIA’s rules.

Keeping track

However, though the 2022 rules represent a phenomenal body of work by both F1 and the FIA, Smedley is under no illusion that teams have little interest in their spirit and will be focused purely on performance. Some of the development paths they take could well reduce the rules’ effectiveness in terms of close competition.

Here, the power of AWS will once again come to the fore, with F1 able to conduct extensive analysis of the huge amounts of data it harvests over a race weekend, harnessing AWS’s AI-driven tools to spot patterns and trends.

Smedley says, “That will give us a lot of insight as to how the teams develop. What is their rate of development? What areas are they’re developing? It will let us see how the 2022 car evolves once we give it to the teams. That insight will then allow us to help the FIA tweaking the regulations going forward.”

Looking even further down the line, Smedley says F1 is also working of developing a proof of concept for generative design development, which could be used to help refine the next major rule set in a resource-efficient manner, in addition to making much greater use of AI-driven data analytics across the board.