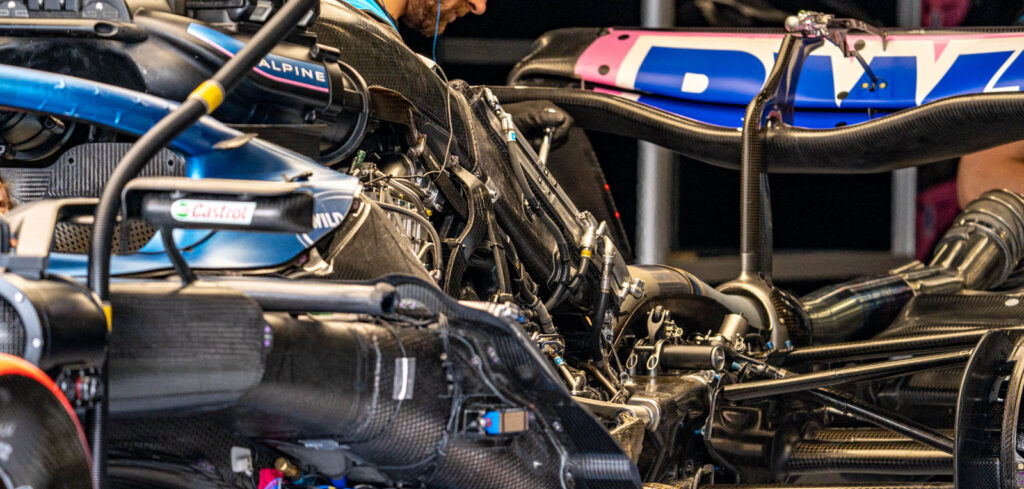

It might seem a long way to go to 2026, but when it comes to developing all-new power units, that year’s rule changes loom large on the horizon for Formula 1’s engine manufacturers (both current and new entrants). Though the basics of the ICE engines will remain the same as those used now, regarding bore, stroke and the retention of a 1,600cc capacity and V6 configuration, the changes mean they will be essentially clean sheet designs.

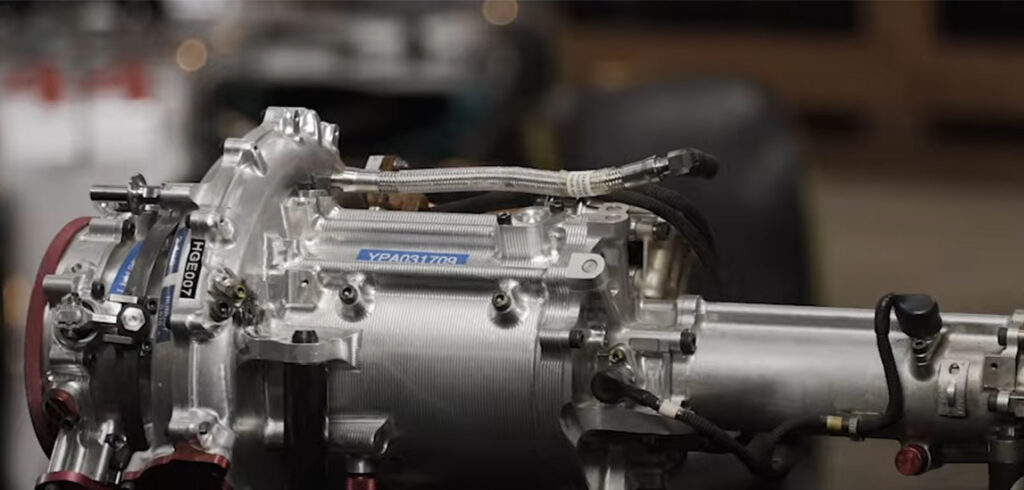

Gone will be the current 120kW MGU-K and exhaust energy recovery MGU-H arrangement, and in their place a far more powerful (350kW) MGU-K, and no thermal energy recovery beyond the use of a conventional, non-electrified turbocharger. The intent is that power delivery will be split 50-50 between ICE and electrical components, and the fuel energy allowable for the ICE will be capped at 3000Mj/h, compared to the approximate 4500Mj afforded under the current 100kg/h fuel flow limit.

PMW sat down with Hywel Thomas, MD of Mercedes AMG High Performance Powertrains (HPP) at Silverstone ahead of the British GP, to better understand the challenge the new regulations present. “I think the exciting bit for these regulations is that they are relevant today. We’ve the still got combustion engine, it’s got the sustainable fuel – and that’s going to be a big part of the challenge – and then we’ve got this significantly larger EV element. Of course, that’s very relevant for the automotive industry,” he said.

Thomas flagged up the loss of the MGU-H as significant, given its key contribution to combustion control in the current generation of very lean running engines. The 3,000Mj energy limit will force manufacturers to further improve efficiency, despite having fewer tools to deploy. “Everyone thinks that the MGU-H is the work of the devil, but actually, it’s a fantastic engineering tool – we probably didn’t talk about it enough. And that’s going away and it’s going to put a real strain on the combustion.”

Reflecting on the development that the 2014 engine rules heralded, Thomas suggested that 2026 will be just as taxing for powertrain developers. “You look back and you think, ‘Crikey, we have some real innovations’. We’re in that same position with the combustion now where we need to make those sorts of steps, that kind of innovation, that kind of work, because it’s a big challenge. And then you start thinking that we’ve got limitations on compression ratio, all sorts of limitations coming on the combustion. Getting the power out from the combustion engine is going to be really important.”

Reflecting on the development that the 2014 engine rules heralded, Thomas suggested that 2026 will be just as taxing for powertrain developers. “You look back and you think, ‘Crikey, we have some real innovations’. We’re in that same position with the combustion now where we need to make those sorts of steps, that kind of innovation, that kind of work, because it’s a big challenge. And then you start thinking that we’ve got limitations on compression ratio, all sorts of limitations coming on the combustion. Getting the power out from the combustion engine is going to be really important.”

The MGU-H is not the only tool that will be lost. Less obvious ones such as in-cylinder pressure measurement are also for the chop. The ability to accurately measure combustion pressures in real time and use this data as an input for closed-loop control of the combustion system has been vital when running engines in the realm between spark and compression ignition.

Despite the difficulties the removal of these sensors present, Thomas is a fan of the rule change: “I think that’s a great regulation because we all spend way too much money [on pressure sensors]: if you just take them away from everybody, it’s fine. We’ll work out a way of controlling the engines that’s far more in tune with what actually happens in the real world. But there are all those pressures that are making it really tough on the combustion engine. I’m sure there’s going to be some great innovation in all the different companies to work out how do we get back to approaching the same sorts of levels of thermal efficiency that we’ve got out the [current] combustion engine?”

Another knock-on effect of removing the MGU-H will be driveability, with the new MGU-K having to take a far greater role in torque filling. While the current H allows for the ICE to be always on boost, regardless of the use of large, and thus efficient, compressors to meet the air demands of very lean running, the 2026 engines will have no such assistance. Max Verstappen has already remarked that early simulator runs using Red Bull’s 2026 powertrain model have been challenging, with full power not available over the entire lap.

Thomas noted that using the (limited) electrical energy each lap to torque fill, rather than augment the ICE at peak power, is not the best use of the energy, but a necessity given the rule constraints. “You won’t get that torque fill all of the time; the other part of that is you’re spending the precious energy that you’ve got on filling in torque [that] you’d really prefer not to be doing. It’s almost not a waste of the energy: you’d really prefer your own combustion engine to be able to deal with all of that and just spend the electrical energy when it’s good for lap time.” He added that the banning of variable-length inlet trumpets will further compound the issue of transient response. “There’s a lot of stuff that’s kind of bunching you into a corner of what you can do, and it’s probably not what the car wants you to do. But then that becomes the challenge.”

Thomas noted that using the (limited) electrical energy each lap to torque fill, rather than augment the ICE at peak power, is not the best use of the energy, but a necessity given the rule constraints. “You won’t get that torque fill all of the time; the other part of that is you’re spending the precious energy that you’ve got on filling in torque [that] you’d really prefer not to be doing. It’s almost not a waste of the energy: you’d really prefer your own combustion engine to be able to deal with all of that and just spend the electrical energy when it’s good for lap time.” He added that the banning of variable-length inlet trumpets will further compound the issue of transient response. “There’s a lot of stuff that’s kind of bunching you into a corner of what you can do, and it’s probably not what the car wants you to do. But then that becomes the challenge.”

The switch to fully synthetic fuels for 2026 adds an extra layer of complexity to the combustion development process. However, Thomas pointed out that fuel partners are still allowed, rather than a spec fuel from a single supplier. Mercedes is already “working hand in glove” with current partner Petronas on the matter. “We want to make sure we end up with a fuel that the engine loves, but that can be produced by Petronas,” Thomas said.

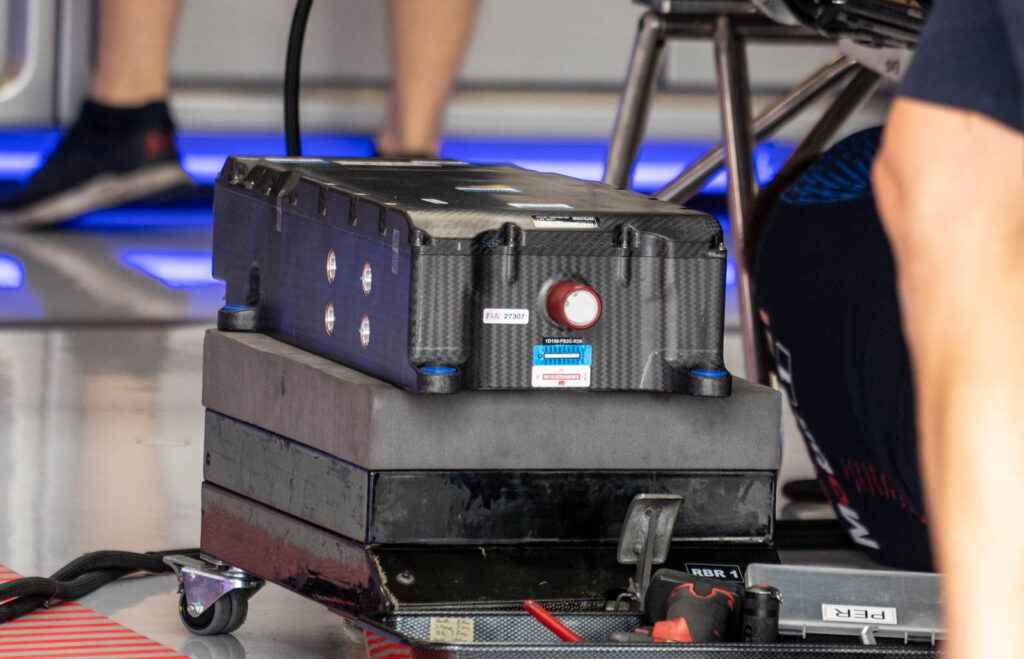

Turning to the electrical element of the new powertrains, this is in some ways the simpler element in the equation. MGU-K power will be capped at 350kW, with a minimum weight for the unit set at 16kg, equating to approximately 21kW/kg power density. This is within the realms of current cutting-edge motor technology.

“The electric motor, I guess, is a competition of efficiency and mass; and there’s a minimum mass,” Thomas said. “I think the technology needed for the motor is probably not that much of a push – there’ll be people in my work who would disagree with me on that one – but it’s a development of the technology that we’re already using. Then we’ve got the battery challenge as well, which is far from trivial.” On this last point, the rules stipulate that battery chemistries cannot be bespoke developments for manufacturers and must be available commercially.

It is still early days for the new regulations, though doubtless manufacturers already have single-cylinder units running on dynos. It will be fascinating to see who steals the upper hand come 2026 and it seems, at least for now, that F1 is once again pushing engine and powertrain technology to new heights.