The Peugeot 9X8 LMH was never going to be ready for the 2022 Le Mans 24 Hours as the French manufacturer originally hoped. Supply chain issues combined with Covid-19 restrictions ensured that the marque’s return to the pinnacle of endurance racing would have to wait another year. In the long run, this was probably for the best.

When the car finally made its debut at the 6 Hours of Monza the following month, before completing the remainder of the WEC season, it was clear that not only did it need refinement, but so did the team. A rushed rollout two months earlier would have been unlikely to improve the situation while locking Peugeot into a suboptimal homologation spec. As it was, the 9X8 made a good showing in Italy, close to the pace and seemingly not displaying any wayward handling traits. However, neither of the two cars was reliable, and watching Peugeot’s pit operation it was evident that the team needed plenty of polish before it was on par with Toyota.

Push to target

When PMW last spoke to Peugeot Sport’s WEC technical director, Olivier Jansonnie, at the 2021 Le Mans 24 Hours, the 9X8’s final designs were about to be released for production and the manufacture of jigs and tooling was being approved. Catching up with Jansonnie in 2022, once again at Le Mans, he highlighted that Peugeot’s timing was unfortunate.

“It was a really tough time as I think every team and manufacturer was trying to do the same thing, there were shortages of materials and components, and on top of that there was still the problem of Covid. It took a massive push from our production department and our smaller suppliers to build the car. We did our first test in December 2021 and that was a very important milestone [to hit].” Peugeot relied heavily on its simulation program, particularly through 2021, with an emphasis on virtual testing of the car using its driver-in-the-loop (DIL) rig. “It was tough because we were developing our simulation and the car in parallel through 2021 and we had about a year of only virtual development. With the DIL, it is not as good as actual track data, but it is very valuable both for development and running of the car,” remarked Jansonnie.

While it was possible to physically test the 9X8’s powertrain off-track, with Peugeot running an extensive test bench program for both the ICE, hybrid unit and control software, Jansonnie suggested that rig testing of chassis- related components was limited. “In terms of suspension and those areas, it is hard to test what you see on track.” You can apply the load cases you expect to see and make sure they match the simulations and calculations, but there are the load cases you may have forgotten or haven’t foreseen. You will only find those on track, or more specifically, during races.”

Clean lines

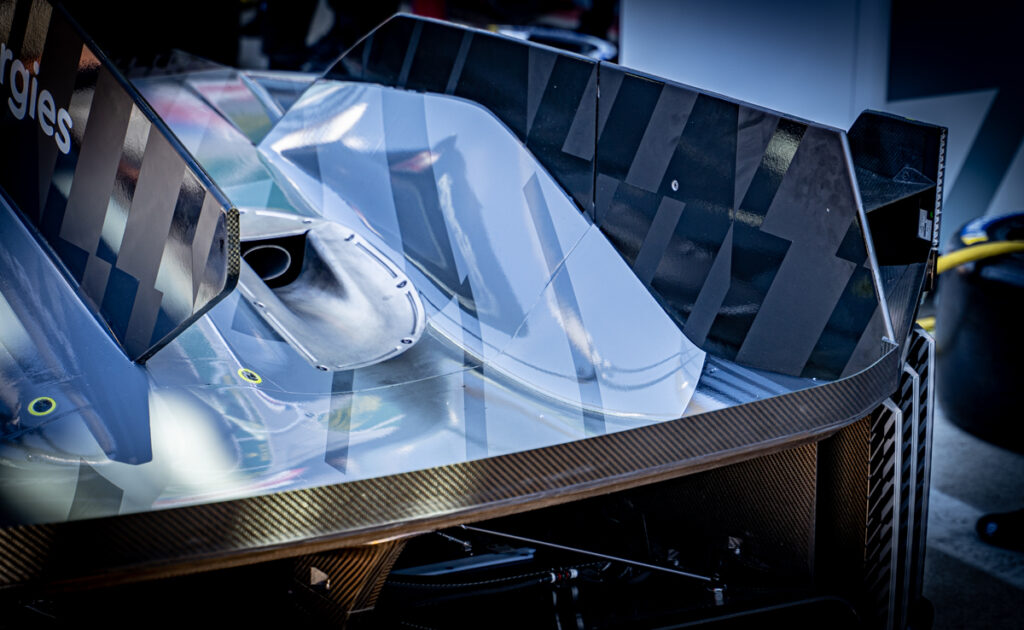

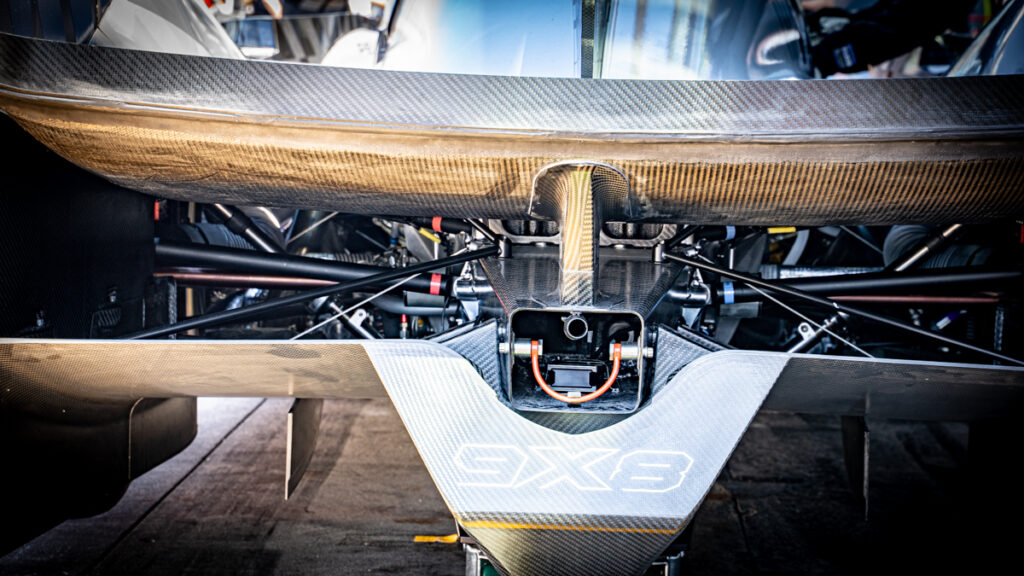

The standout feature of the 9X8 is clearly its lack of a rear wing, which caused a few raised eyebrows when the car first appeared. Jansonnie was coy about revealing too much detail surrounding the car’s underfloor design, but explained that the concept was made possible thanks to the greater freedom afforded by the LMH rules compared with LMP1. He noted that the center of the floor was now able to contribute a much greater proportion of downforce than previously, though the rear diffuser remained quite similar in performance to the previous generation of LMPs.

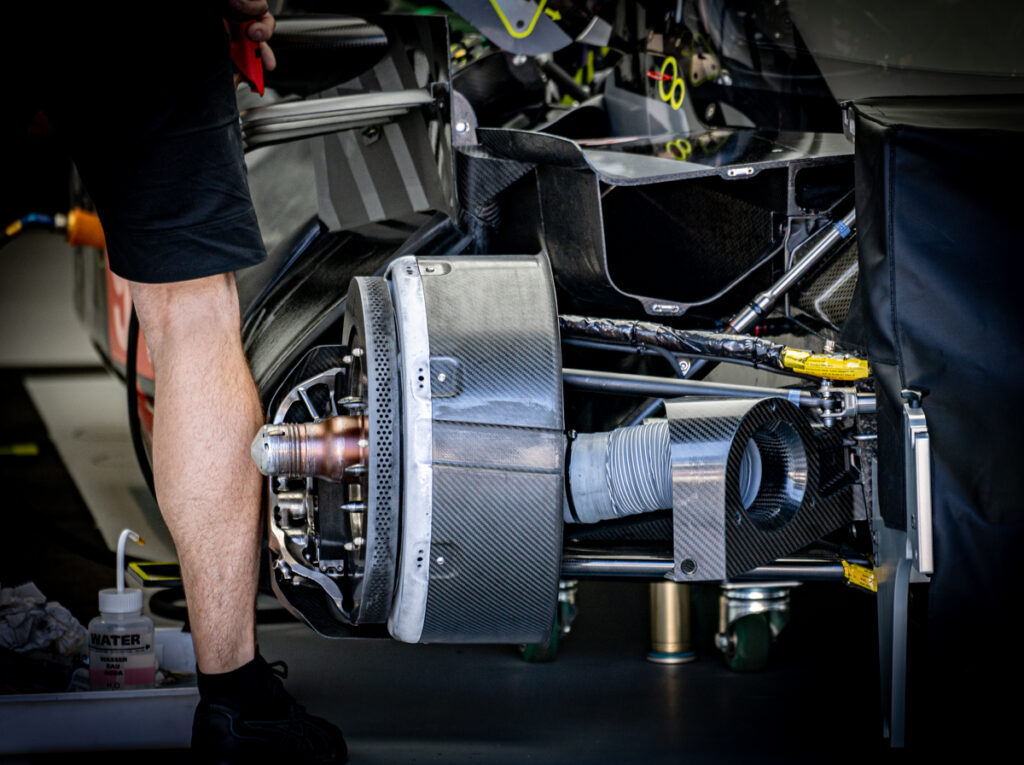

Fortunately, scrutineering at Monza afforded an opportunity to look under the 9X8, which revealed relatively modest underfloor tunnels, albeit with some interesting treatment of airflow coming off the front underwing. That Peugeot could do away with a wing was not solely down to regulatory freedom, but also the conservative aero targets set by the BoP and homologation process. Jansonnie quipped, “If we had a rear wing on this car, we would generate more downforce than we could use.”

To balance the car aerodynamically, the rules permit a single adjustable device to be used, fitted to either the front or the rear. To this end, the 9X8 features a single adjustable element on the front underwing, which is almost seamlessly blended into the main wing structure. Adjustments are made via securing struts at either outboard end of this section. To ensure that sufficient balance adjustment was available, Peugeot conceived three solutions during the car’s design phase. Jansonnie stated that its primary choice was always an adjustable front element, which showed the best potential in both CFD and wind tunnel analysis.

However, it was only once track testing commenced that its effectiveness could be confirmed. The reserve alternatives relied on the rear Gurney flap that runs along the trailing edge of the bodywork, with options to make this either height or angle adjustable. “With everything on the car, we have a primary option, which is our reference solution, fitted to the car when it hits the track, and backup options. We ascertained when the latest point would be that we could switch direction, but fortunately we didn’t have to go that way,” said Jansonnie.

Observing the car at Monza, which is an admittedly relatively smooth track, requiring low downforce, the car did not seem to display any unpleasant traits. Watching through Ascari corner and the high-speed Parabolica, the 9X8 at all times remained well composed, an observation also reflected by in-car footage. However, the breadth of track types visited over the course of the WEC could yet push Peugeot’s setup into uncomfortable territory. In terms of ride height sensitivity being a greater issue due to the reliance on the underfloor, Jansonnie said, “It’s different in the way it behaves, but I wouldn’t say it is more or less sensitive [than a conventional car]. We must have some humility and recognize we have only run on some tracks – but so far, we haven’t found anything that makes it very different to cars we have run in the past.”

Weighty matters

It is notable that the rules do not place any limitations on weight distribution (as is the case in series such as F1); however, once a car is homologated, the distribution can only be adjusted by ±0.5%. This has the potential to create problems related to BoP, which allows for a car weight of between 1,030kg and 1,080kg, meaning Peugeot and all other teams must account for potential additional ballast placement early in the design stage, while staying within the distribution window.

“It’s a very difficult exercise and you have to plan well in advance of homologation,” pointed out Jansonnie. While not willing to divulge its exact weight balance, Jansonnie suggested that the car was designed from the outset to run equally sized tires all around (31/71 x 18), as was specified by the rules for hybrid cars when Peugeot commenced work. The entire concept therefore centered around making these tires work, which he said requires a near 50:50 weight distribution. However, the rules were later changed to allow 29/71 front and 34/71 rear tires, which Toyota took advantage of with its reworked GR010 in 2022. Clearly, the use of a larger rear tire benefits both grip and wear over a stint.

For Peugeot, the change came too late. “We would have had to redo everything, and we wondered for some time whether we should accept a delay in the project and start over again,” Jansonnie recalled. In the end, it stuck with the previous tire specification and Jansonnie said it was assured that performance would be balanced regardless of tire size, saying, “We are all in the same boat and we have to make it work.”

With a hefty minimum weight, it was apparently relatively easy to design a car with scope for ballasting, and Peugeot had an easier job than Toyota in this aspect. The latter’s design tied into earlier rules relating to minimum weights for components such as the hybrid motor. These constraints were later removed, with Peugeot early enough in its design cycle to take advantage.

Outlining Peugeot’s approach, Jansonnie said that it started out with the lightest concept it could (within reason), then reinforced areas that presented problems during testing. “The car has got heavier through testing, but we feel it is much better to start with a light design and reinforce, rather than the other way round. Shaving weight off a car is very difficult and expensive. It’s a bit scary to begin with because you keep breaking parts until you reach the right level,” he explained, adding the caveat, “Maybe we are still not at the right level: only racing will tell.”

Decoupled suspension

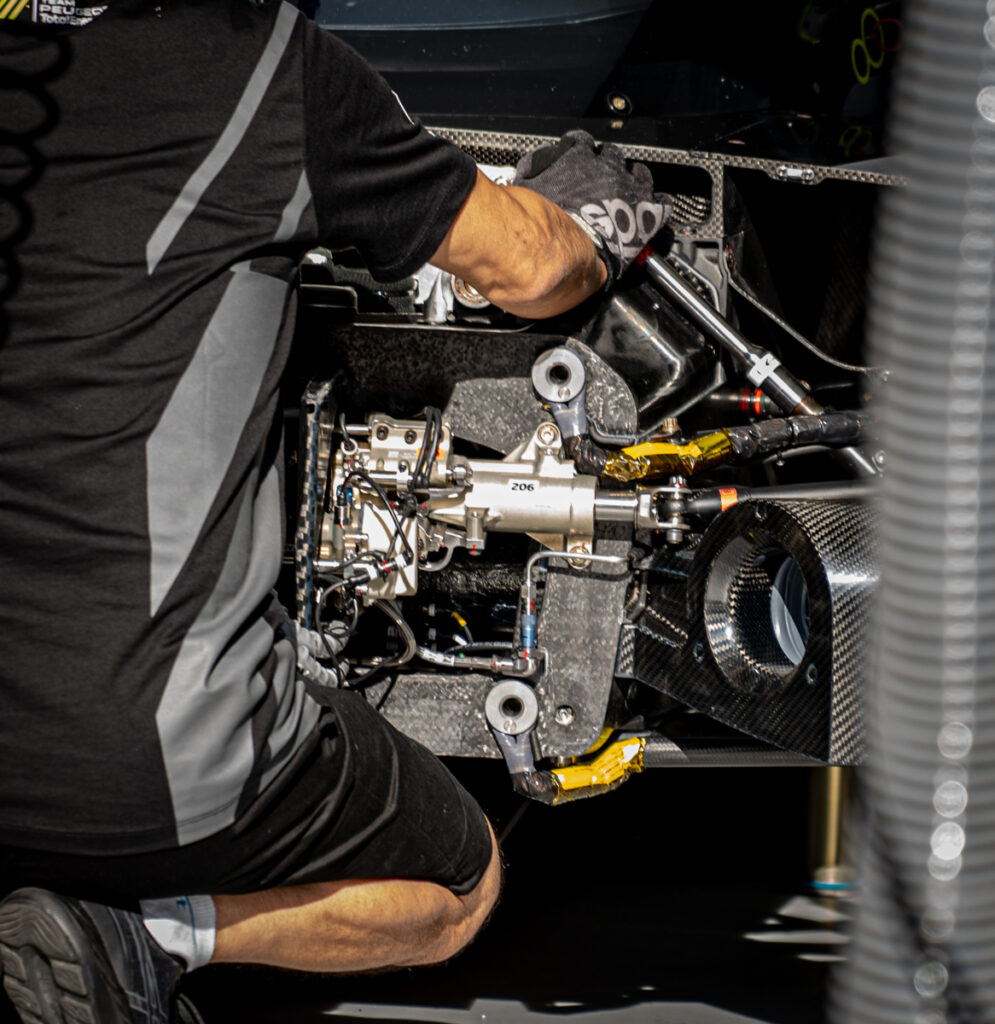

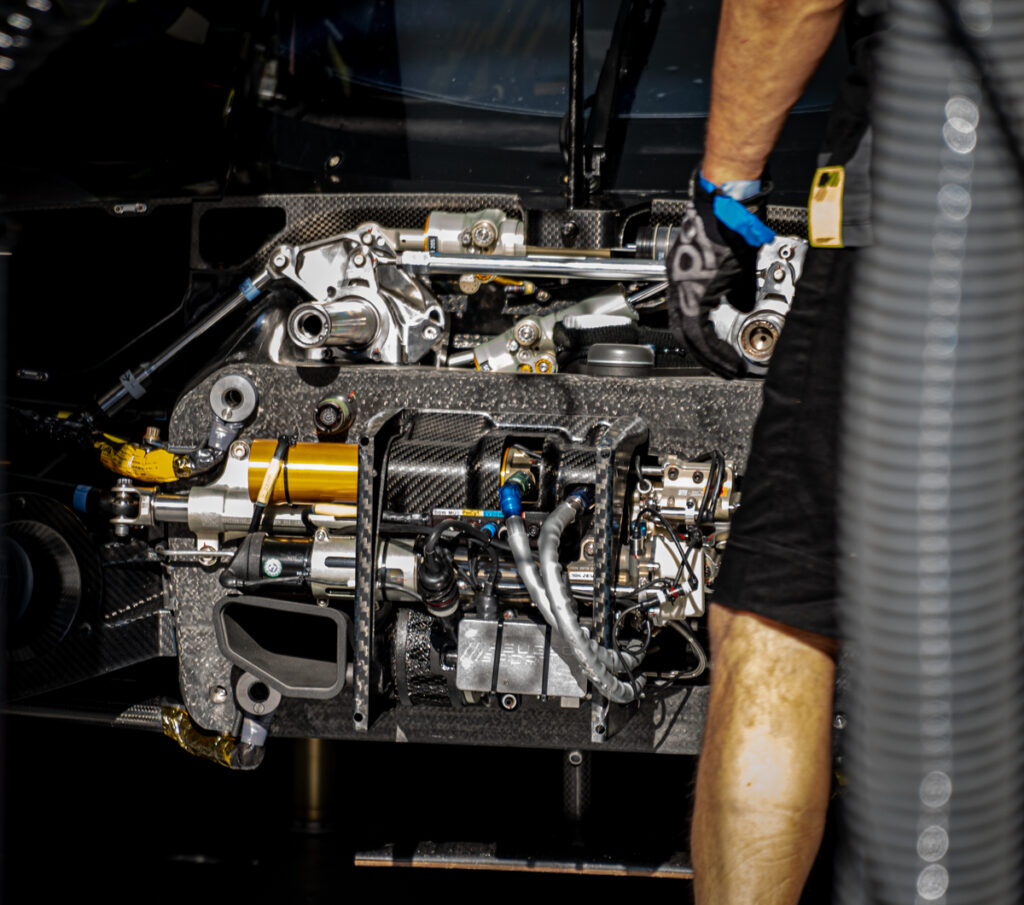

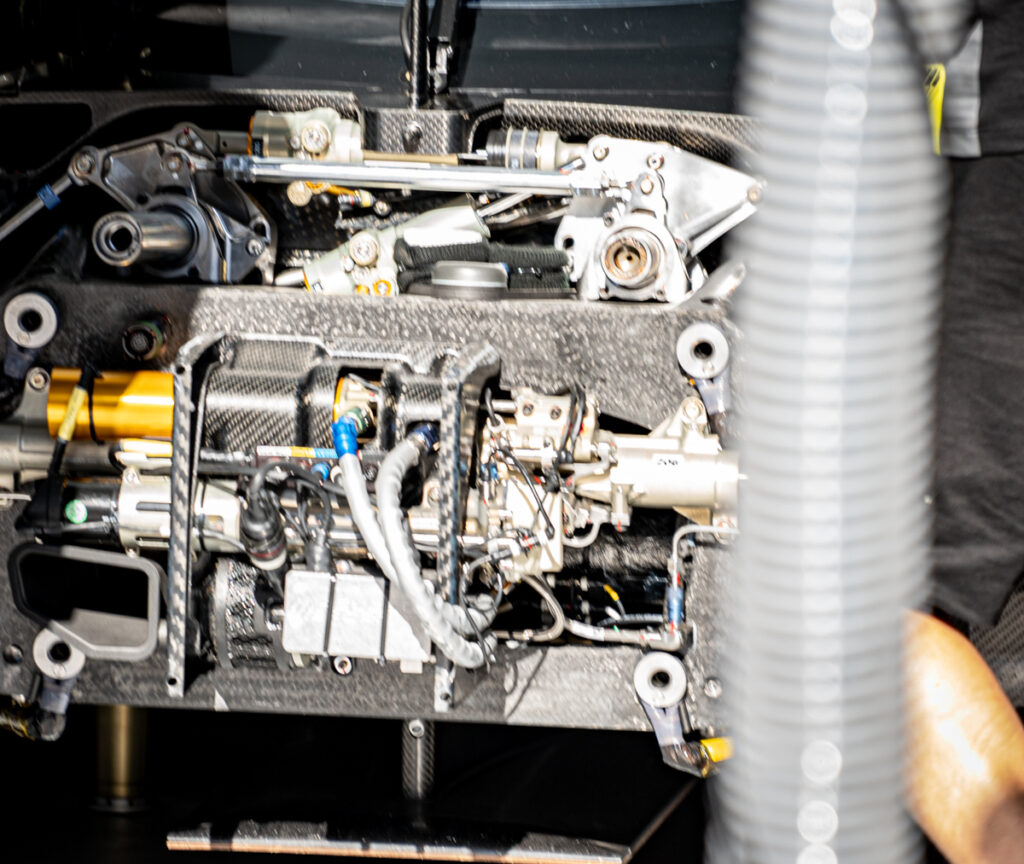

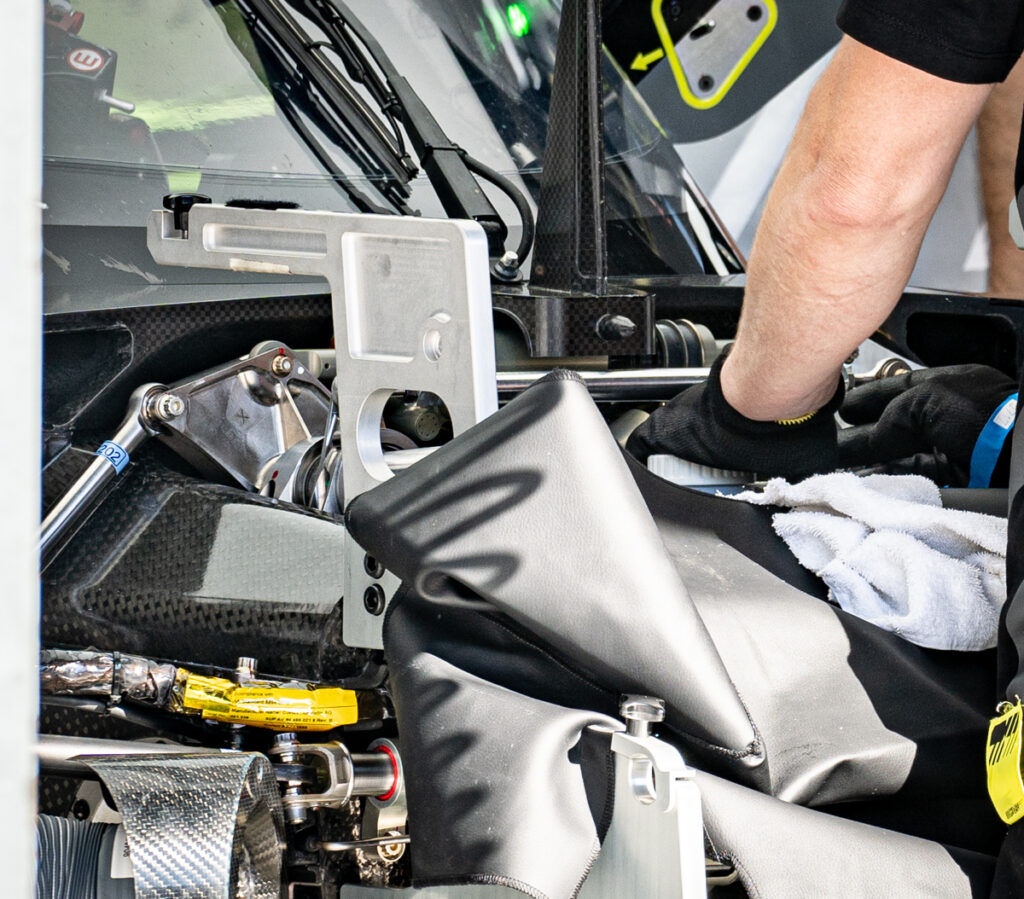

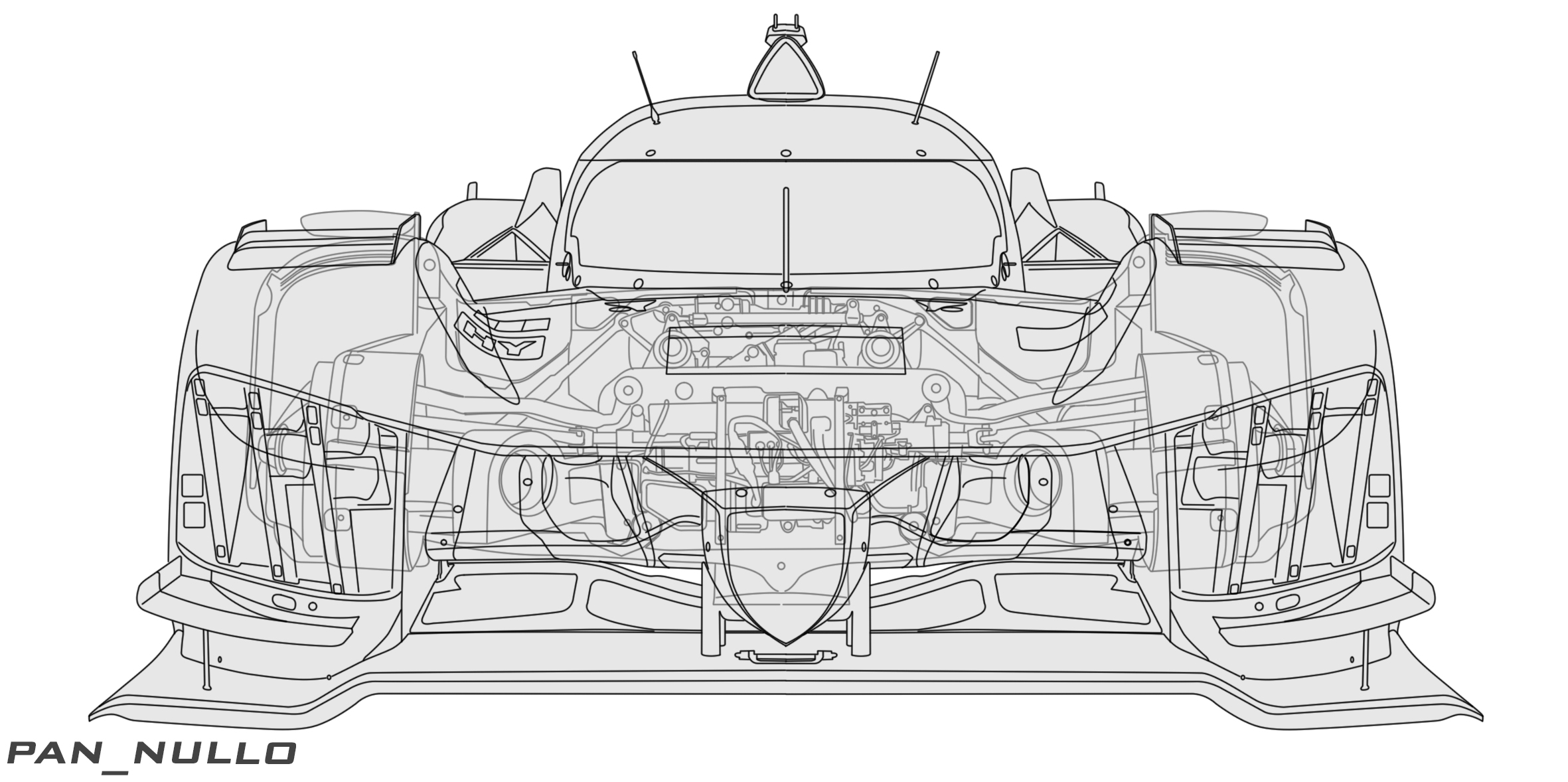

One area of note on the 9X8 is its front suspension, which the team was at pains to keep covered up during the car’s debut. However, PMW was able to obtain clear photographs, which suspension engineer and motorsport consultant Andrea Quintarelli was kind enough to provide comment on.

“Peugeot seems to have adopted a concept that appeared on F1 cars some years ago, which seeks to decouple roll and heave. The layout employs two rockers, one on each side of the monocoque, with a heave damper mounted on top and a roll damper installed diagonally between them. In heave, when the two rockers rotate in opposite directions, the third damper is compressed and its length is reduced; in this scenario, the roll damper does not change in length and it does not produce any action.

“In roll, when the two rockers rotate in the same direction, the opposite happens: the heave damper does not change length, because the pickup points where it is attached to the rockers move more or less horizontally, an equal amount and in the same direction. The roll damper, on the other hand, is compressed or extended, due to it being attached to the top of one rocker and to the bottom of the other, thus its length changes when the rockers rotate [either] clockwise or counter-clockwise. The end result should be an effective separation of damping control in both heave and roll.

“Roll is likely controlled by an anti-roll bar, located on the lower part of the monocoque. A neat feature is the rod that connects the two torsion bars via mounting ‘ears’. The two torsion springs do not appear to be grounded on the monocoque, which would provide a wheel rate as a consequence of them twisting relative to the chassis.

“Rather, they are locked together via a rod. This effectively neutralizes them in roll when the two bars, rotating more or less equally and in the same direction, do not experience any twist. In heave, the two rockers twist their respective torsion bars in opposite directions, counteracting the rocker’s rotation, providing a pure heave spring effect. Another pleasing side effect of this design is that two torsion bars of different length and stiffness can be used on either side of the car, in order to achieve the desired overall wheel rate.”

A full, indepth description of the system can be found on Andrea’s blog, here:

Powertrain

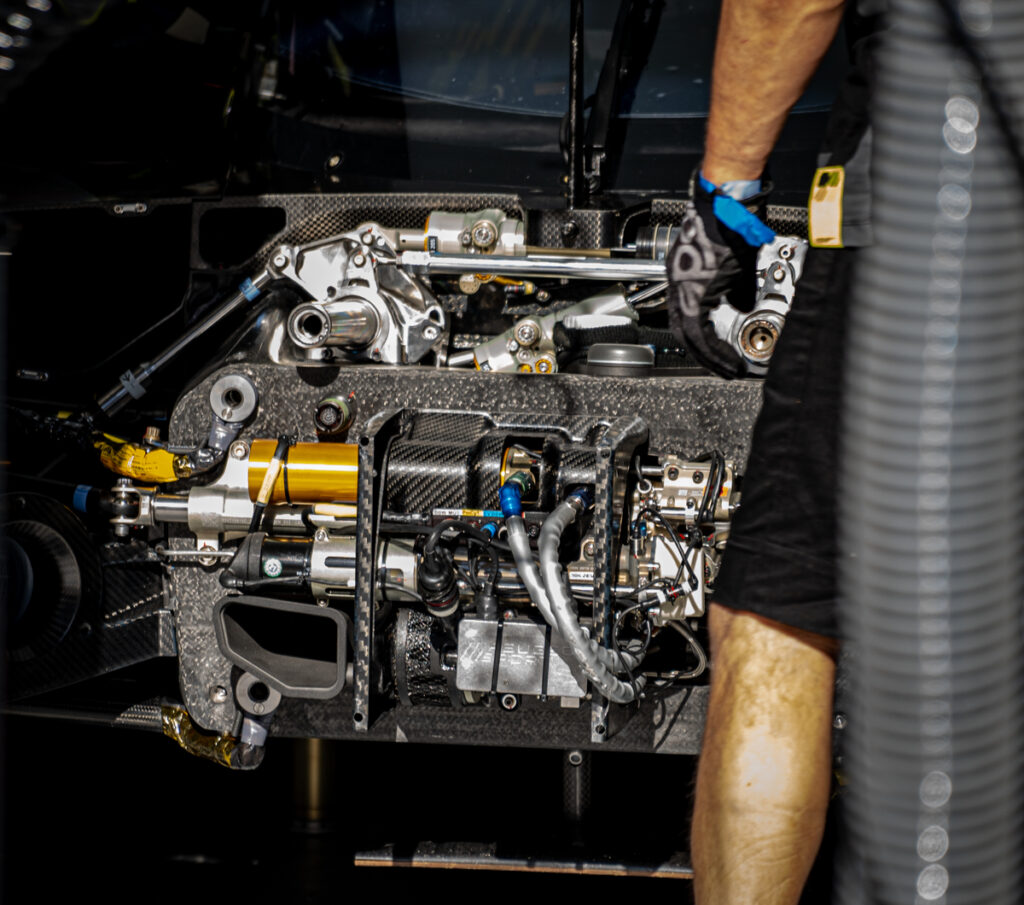

The 9X8 runs what Jansonnie said is an entirely in-house-developed powertrain, consisting of a twin-turbocharged, 2.6-liter direct-injection V6, married to a 200kW front-mounted electric motor-generator. As per the LMH rules, total output of the powertrain is limited to 500kW regardless of the combination of ICE and hybrid used (the rules had initially stated an output of 580kW but this was dropped to help alignment with the LMDh rules).

Initially, the rules also set a minimum weight for the engine of 180kg, but when the power requirement was lowered so too was the weight of the engine, to 165kg. According to Jansonnie, development of the ICE drew on Peugeot Sport’s experience stretching right back to the diesel 908 LMP1 days, with a target of producing a compact and power-dense engine and transmission, which would afford greater packaging freedom at the rear of the car.

“Even though the 908 was a completely different concept we were able to carry some ideas over from that time,” he said, adding, “There are also elements from our WRC and WRC projects; for example, the engine’s combustion chamber concept. It is a melting pot of ideas from other projects in the group.”

One tweak to the BoP regulations has caused some controversy with hybrid LMH manufacturers: the speed at which the hybrid (and thus four-wheel drive) can be deployed. Initially, this was set at 120km/h regardless of car; however, to help achieve parity with the two-wheel-drive-only LMDh cars, it has become a variable. Though BoP is normally balanced with weight, in wet conditions four-wheel-drive machinery will invariably have an advantage, hence the pressure to remove said benefit. In the case of Toyota, deployment is restricted to over 190km/h; for Peugeot, 150km/h at its debut race.

This rule appears to remove any advantage of carrying a hybrid, though Jansonnie was philosophical about the situation. “Raising the ERS deployment speed was theoretically the easiest way to balance this, but I would say it is not our favorite option. There was a huge discussion, as you can imagine.” As to whether there remained any benefit to having a hybrid: “It’s a difficult question. Motor racing these days, for manufacturers at least, is electrification, it is hybridization. That is the story we want to tell. For performance, it will be up to the governing bodies to decide but, if you set the deployment speed very high, it becomes electrical ballast.”

The 9X8 is undoubtedly a competent race car and so far (judging by images of Ferrari’s 2023 contender) the best example of the design freedoms afforded by the LMH rules. However, if Peugeot wants to attain glory at Le Mans and across the WEC season, both car and team must deliver against what will be stiff competition.