Though no longer majority owned by its parent Formula 1 team, UK-based Williams Advanced Engineering (WAE) is still extensively involved in a variety of motorsport projects. These include supplying battery systems to the Extreme E off-road championship as well as developing Formula E’s Gen 3 battery system. The association with racing, as technical director Paul McNamara explains, is integral to the company’s ethos.

“We set up WAE as an offshoot of Formula 1 and inherited a lot of battery and electronics capability from that. Electric motorsport is a logical place for us to be and the thinking is that if we go for electric motorsport, that gives real-life experience and a halo effect, which pushes us in performance cars and beyond,” he says.

WAE’s first high-profile EV motorsport program was the Gen 1 Formula E battery system, which debuted back in 2014, and built on experience gained in F1 with KERS. Since then, the company has established itself as one of the go-to sources for series looking at electrification and as McNamara outlines, WAE’s approach to motorsport batteries has evolved as the available technology and demands of manufacturers have advanced. “Being involved with Formula E for the first four seasons, then the links with Jaguar [also in Formula E] and now doing the Gen 3 battery have been important. Extreme E is the next step on from that.”

Given the rigors of its latest work with Extreme E – remote races in inhospitable climates and minimal access to infrastructure – the company has had to adopt a different battery philosophy to previous projects, where it has always been possible to factory service batteries. “We have always been quite passionate about the usability of electrification, because one of the problems with electric vehicles is that they are not as flexible as an IC engine,” muses McNamara. “You can’t carry around a can of electricity. Extreme E is starting to push those boundaries. We thought we couldn’t really bring through Formula E tech or other motorsport ideas. The driver was not just robustness, but being able to take the battery apart easily, everything had to be simple. A couple of technicians in a tent could take the thing apart.”

Real-world lessons Its involvement across a diverse range of projects means WAE now has the best part of a decade’s worth of data to inform its development activities. “Racing is actually a very good testbed, because it is a relatively controlled environment,” points out McNamara. “During those first four seasons of Formula E, we were getting a constant flow of data from the batteries. The reality was that in the first couple of years, we were doing quite a few repairs on the batteries, looking at them post-race, refurbishing them and putting them back in the cars for the next race.”

The main issues centered around the cooling system, the robustness of the joining methods used for the cells and minor leaks within the internal pack coolant circuits. All of these were logged, and engineers were able to leverage the data to prevent issues recurring. “An algorithm we developed took that information and used it to forecast when we needed to change something, based on the data we collected. That allowed us to develop a pre-emptive maintenance regime between races,” recalls McNamara.

Mass efficiency The competitive nature of motorsport also provides an ideal environment to galvanize rapid development. “The other aspect [of motorsport involvement] has been learning where we can push the limits,” says McNamara, highlighting mass reduction of battery systems as an example. “With a battery, there is a lot of current going through bars of copper. We started to learn where we could use less [copper], by having a lower cross-sectional area for a given current, while balancing heat generated in the copper versus heat in the cell and the cooling system. From that we could also work out where we could have less cooling. All of that has driven down the weight of the packs.”

He points out that only 60-70% of a motorsport battery pack’s mass is the cells, with the rest accounted for by ancillary parts: “It is the other stuff you can optimize. Obviously, the cells are getting better and better, but that is not our core tech; we take the cells and optimize the pack, making the weight and volume more efficient. That’s one of the most dramatic things from Gen 1 through Gen 3 [in Formula E] – how the volume of the pack has come down while giving more power.” Building blocks When developing batteries for new applications from scratch, WAE has a number of core designs it can draw upon.

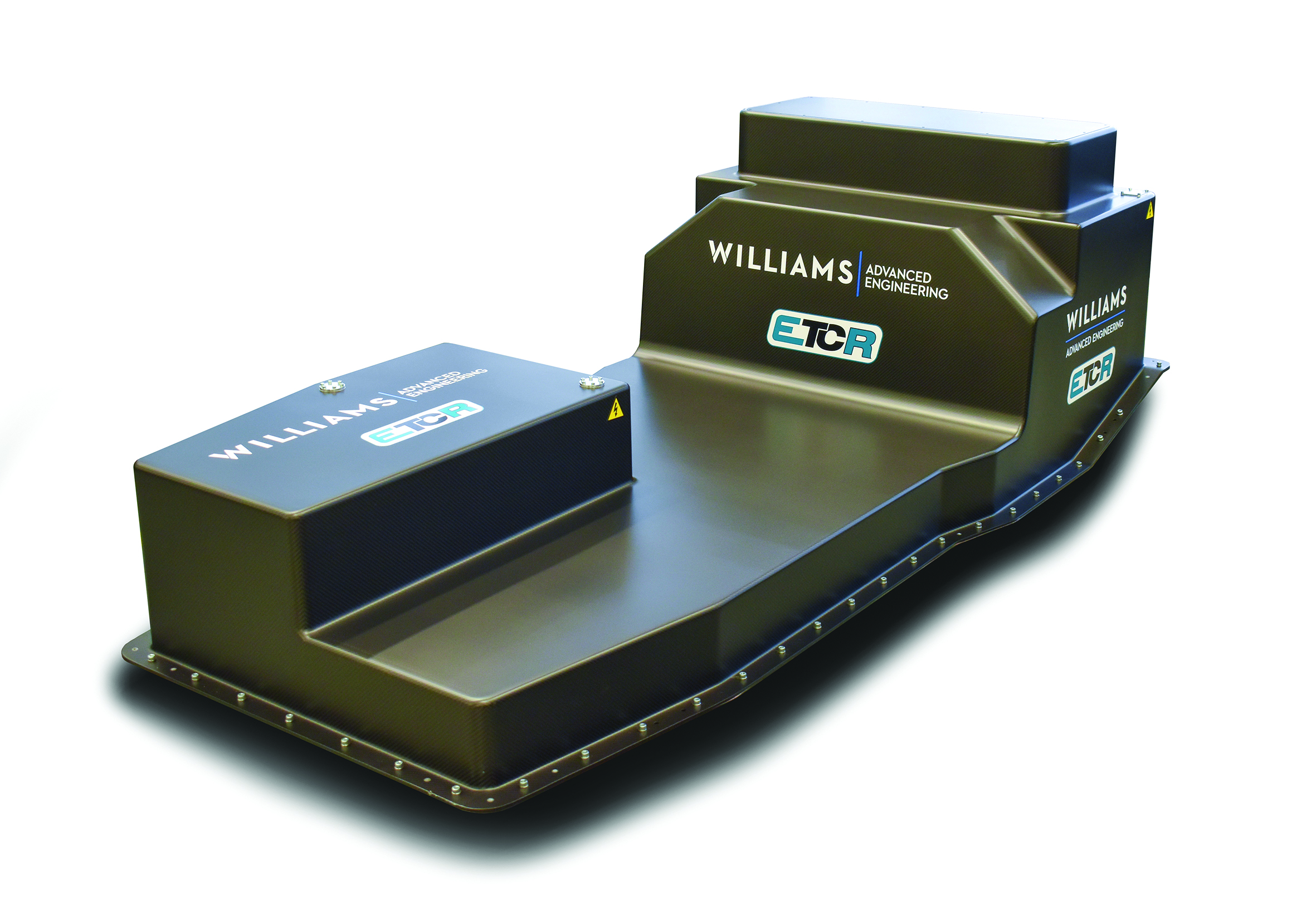

“We have three building blocks,” outlines McNamara. “The first is our Gen 1 module with 32 x 21700 form factor cells in it, which has been used in a number of programs, including currently in ETCR. There is quite a lot of technology involved in a module like that; you have to make it light, think about propagation of any thermal runaway, and manage the welding and process. One of the problems with these packs is you have cylindrical cells, with thousands of welds, so you have to validate for production in what is really an off-the-shelf pack.” Moving up the scale is the so-called Supercell. “That is used in Extreme E and is a holder that houses a number of cells which can then be bolted together. That is the building block of the Extreme E battery and is an air-cooled unit,” says McNamara. “We then have what we call internally our generation 2 module, which is a big module with a bimetallic bus bar and thermal management through integrated cooling and its own controller. That forms one of the building blocks for various other projects.”

Finally, the company has a pouch cell module, which is to be used in the Gen 3 Formula E battery. When it comes to cell technology, the application dictates not just the chemistry but also the cell type used, notes McNamara: “It is that balance between industrialization and outright efficiency. What are you trying to achieve? There are now factories producing cylindrical cells of good quality, but there are a number of pouch cell manufacturers that can give very bespoke chemistries so you can get better energy or power. You can sometimes get better power-to-weight ratios with pouch cells, not just because you don’t have the weight of the canning, but also in how you can package them to get an overall better application.”

Physical testing In terms of development and validation of its various packs, WAE understandably leans heavily on virtual testing to ascertain the predicted limitation across the range of conditions they will experience. “Its always the high temperatures that will prove the problem,” says McNamara, though ultimately physical validation is always required. “We have vibration rigs, thermal chambers; we will deliberately short circuit them, that sort of thing. The standard, UN38.3, has a series of tests which are relatively extreme, and we will run through those, but we also have some bespoke tests developed on the basis of what we simulate a car is likely to go through. We also look at the expected cycles and run them repeatedly though those. There will always be difficulties along the way and we will have to go back around the loop.”

Finally, there is the issue of sustainability in electric racing to address. While it is all well and good being zero emissions, beyond a few platitudes about second life battery use, it is not a widely covered topic. However, for McNamara and WAE, it is a primary consideration for all of its products. “For us, everything we do in terms of sourcing is tightly controlled, making sure the various standards are met. Happily, in the case of Extreme E, the objectives of both recyclability and maintainability collide,” he explains. “What you have is a pack that is very easy to break into its constituent parts. The copper, other metallics and carbon fiber can all be recycled normally, then you are back down to your base cells, which can either be second lifed, or go off to be recycled to raw materials.” <