When F1 underwent its sweeping regulation changes in 2021, they included the introduction of a swathe of spec parts; some constructed by teams, others by nominated third-party suppliers.

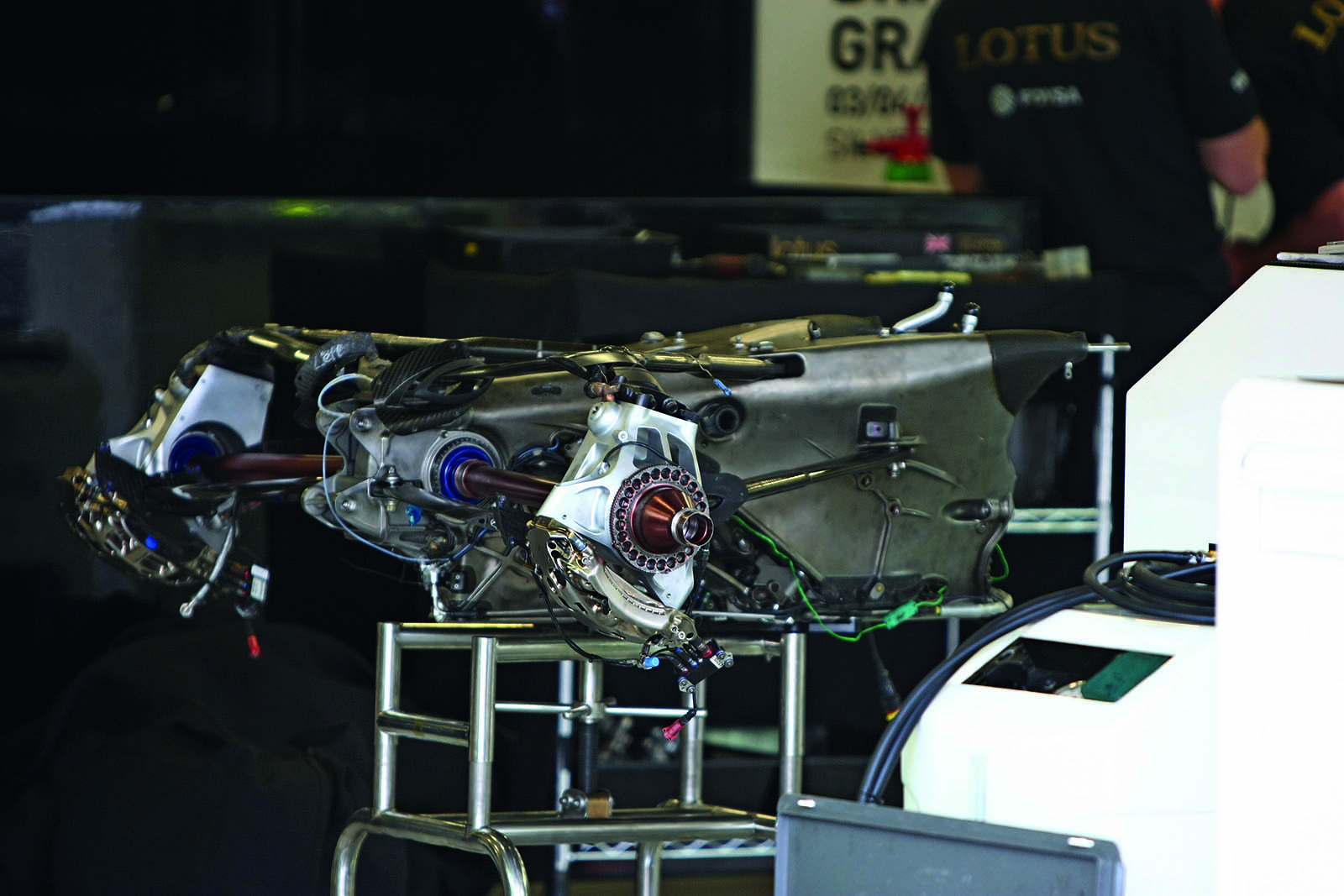

In the extended horse-trading between teams, F1 and the FIA, one of the proposals that did not make it to the final rules package was the imposition of a spec transmission, or more precisely, transmission cartridge. This idea was floated due to transmission development being an area where teams invest considerable resource for small performance gains, yet one that adds nothing to the ‘show’ for fans. Ultimately spec transmissions were canned, but Aston Martin has brought the subject to the fore again for 2026.

When the idea was initially fielded, the FIA went so far as to issue a request for tender, with UK-based Ricardo one of the companies submitting a proposal. What would have been involved in taking on the gearbox supply for the entire Formula 1 grid, catering to some of the most demanding customers in motorsport? Outline requirements

Outline requirements

The FIA’s tender document did not dive into intricate detail on the transmission design that would be required, but rather provided an outline of the basic specifications which would be fleshed out later.

The key consideration was that the transmission be easily adaptable to any team’s individual chassis design, with the tender stating: “The aim of single-source supply is to retain current levels of Formula 1 gear change performance for all cars at a much-reduced cost to the competitors, while also removing the requirement for teams to design or source their own gearboxes.

“The unit can be carried over between seasons, so removing the need for costly continual performance development. In order to retain the competitor’s own freedoms for suspension and for the gearbox aero surfaces, the outer housing will remain team-specific (designed and produced by the competitor) with the common, self-contained gearbox cartridge mounted inside.”

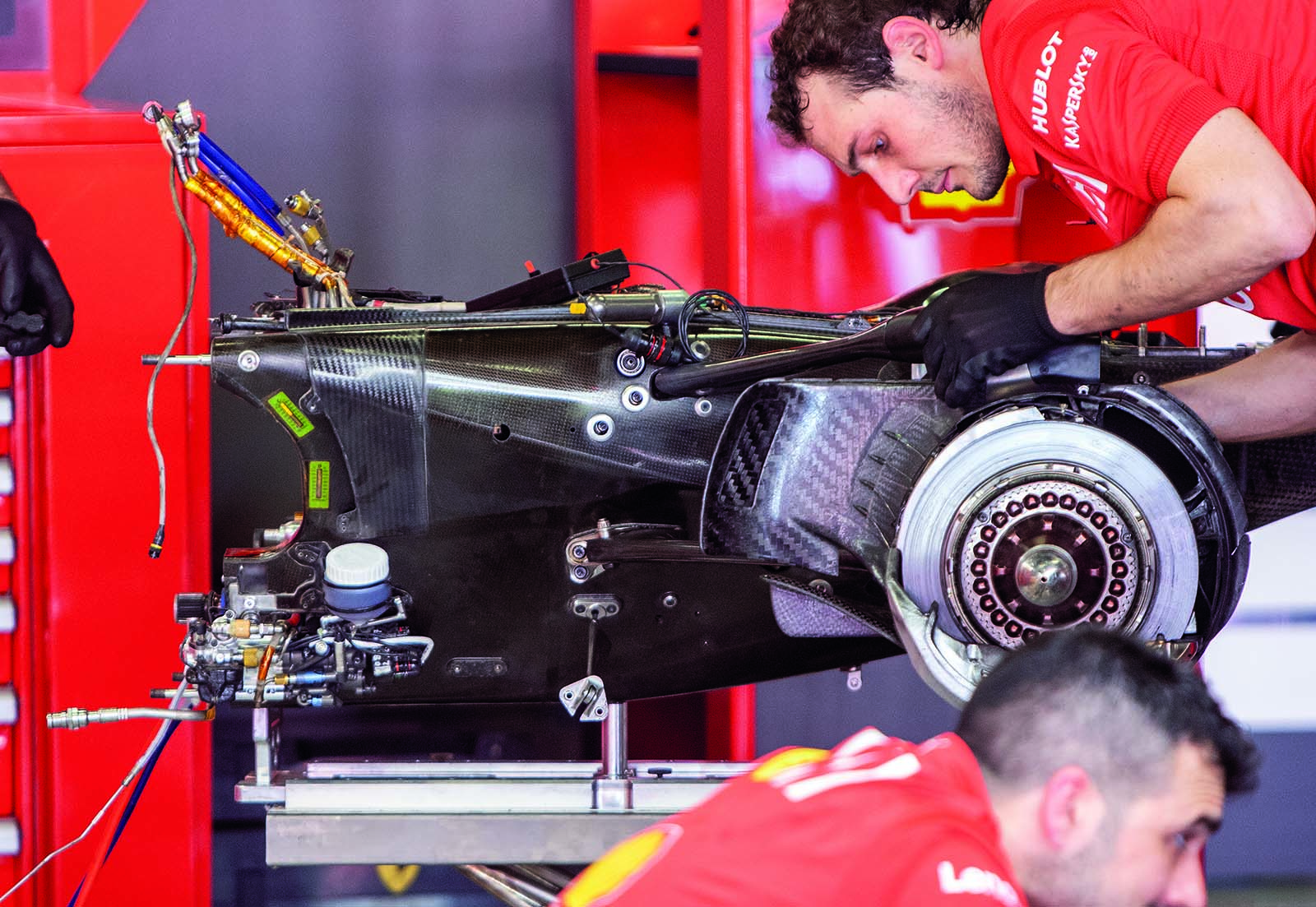

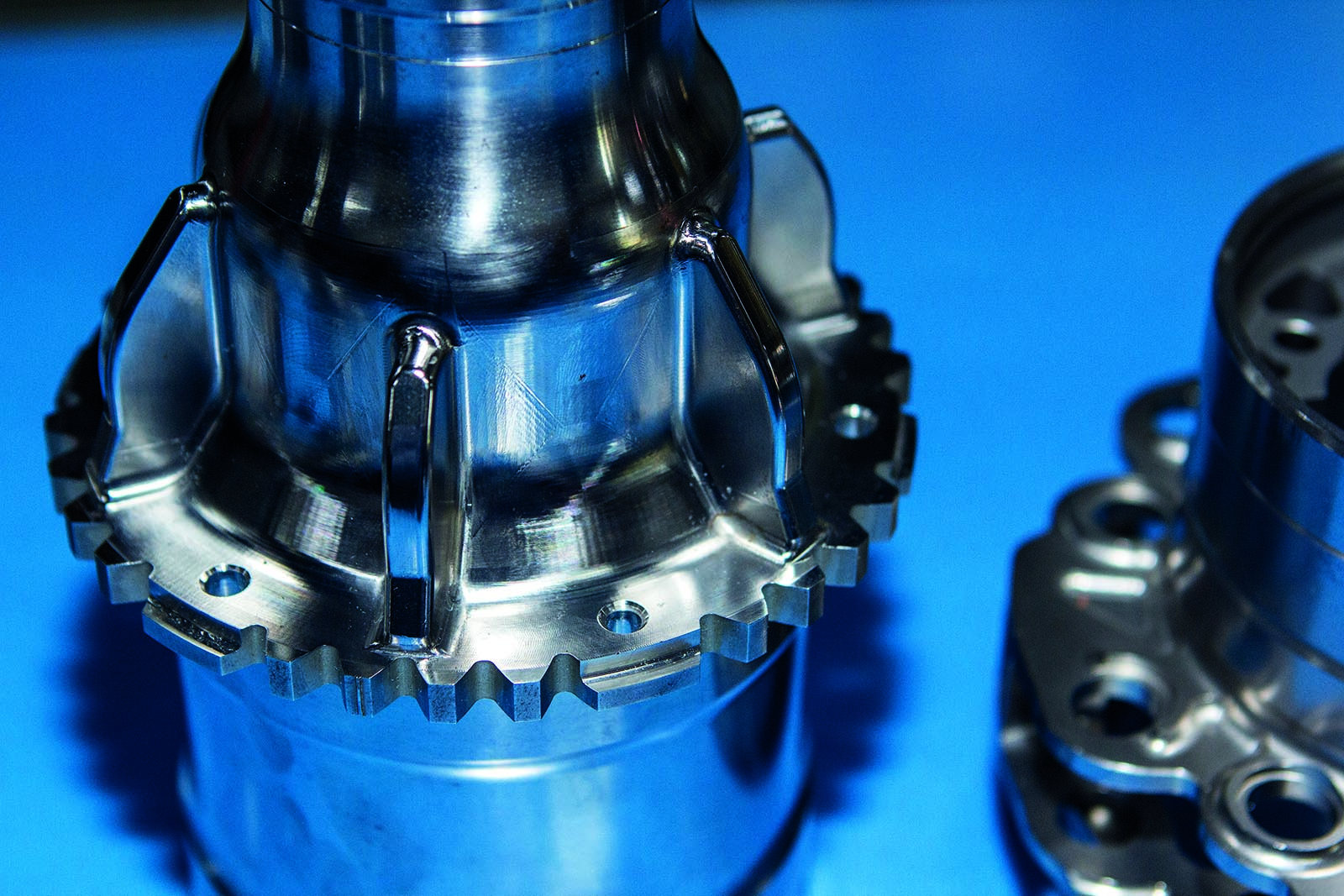

The use of a cartridge gearbox theoretically made life straightforward for the teams, and for whoever ended up constructing the transmission. According to Tim Gee, technical director at Ricardo Performance Products, the cartridge design was necessary to allow easy adaption between teams. “The approach would only work with a cartridge-type box. But it was interesting for us to learn some way down the road that there were only two manufacturers using cartridges. It was a bit of a surprise that not everyone was using them, as for those not running them, it would be quite a step change.” Other specifics of the tender included the need for a 7-speed transmission (a change from the current 8-speed units), along with a minimum quantity per competitor of eight transmissions a season and two test units. Transmissions would also have to be made available to power unit manufacturers.

Other specifics of the tender included the need for a 7-speed transmission (a change from the current 8-speed units), along with a minimum quantity per competitor of eight transmissions a season and two test units. Transmissions would also have to be made available to power unit manufacturers.

Predicting a performance increase over today’s power units, the FIA specified that the transmissions must handle a 15% higher input speed than currently and also accommodate an increase in MGU-K power output of 30kW (from 120kW to 150kW). Interestingly, gear ratios would be homologated across the entire field. Currently, each team homologates its ratios for the year, thus this change would mean a marked restriction of flexibility for teams.

The challenge

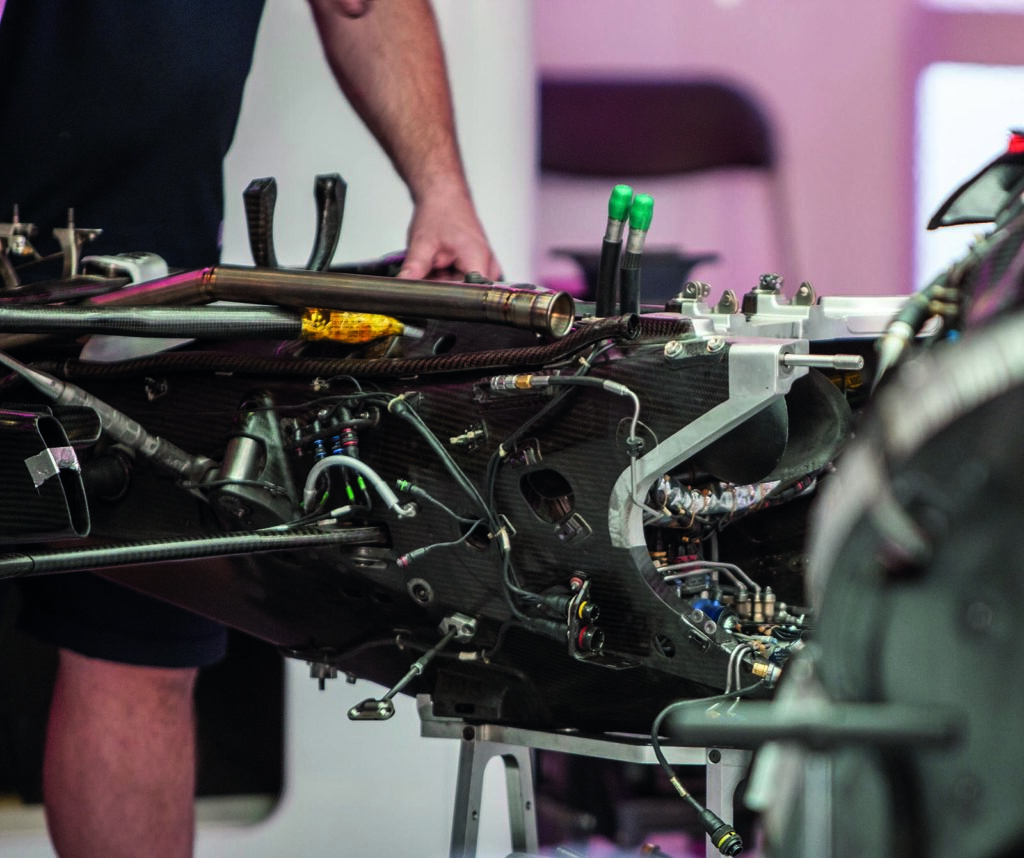

Ricardo currently produces a large number of transmission components for F1 teams; however, it does not manufacture entire gearboxes – no external supplier does. Instead, the bulk of its work is ‘make to print’; teams design their own transmissions, then outsource the manufacture to specialist companies such as Ricardo.

Ricardo designs and builds entire transmission assemblies for other applications: its gearboxes have won multiple Le Mans 24 Hour races, for example. However, in order to meet the brief to supply a cutting-edge (by F1 standards) product, it would have needed external input.

“If we were going to embark on the process, we would have had to align with some partner teams. Of course, we can design a gearbox, but how close would that be to current state-of-the-art solutions? To ensure that, we were going to partner with a team,” says business development director James Sundler.

Even a company such as Ricardo, which is heavily involved in the manufacture of transmissions for teams, rarely gets to see the overall concept within which the parts it produces fit. In fact, according to Gee, the tender process gave a proper glimpse of what actually constituted the state of the art, from which it could form the foundations for its tender design.

“We could then head in whichever direction was most appropriate, be that making certain parts heavier, lighter, adding greater longevity: whatever people wanted. But it was establishing that entry level that was key. If you just started from a blank sheet of paper, you would probably end up some way off the mark.”

Layout

The final transmission design, had it been adopted, would need to be produced in considerable volume and also with a strong eye toward price. After all, the main intent of the move to a spec transmission was cost control. With this in mind, Ricardo settled on a thin wall aluminum casting for the main casing, which would incorporate all of the mounting points needed to fit each team’s car and provide the best balance between cost and performance.

Regarding the casing design, Gee points out that there would have needed to be a degree of standardization in how teams fixed the cartridge within their own housings, otherwise the exterior would be a mess of different mounting bosses.

Additionally, the different characteristics of the various power units would need to be accommodated. Though built to a similar specification, each has its own power curve and, more importantly, a unique vibration signature which must be accounted for in the transmission design. In the former case, by ensuring that the gears, shafts and bearings were sized to accommodate the worst-case scenario from a torque perspective. For the latter, the FIA proposed that input shaft length be varied from installation to installation to allow adaption to the different harmonics. If the design had come to fruition, says Sundler, “There was an extensive validation program as part of our tender response, which involved both rig-based testing and also, where possible, running the transmissions with full PUs, and identifying any potential integration issues.”

If the design had come to fruition, says Sundler, “There was an extensive validation program as part of our tender response, which involved both rig-based testing and also, where possible, running the transmissions with full PUs, and identifying any potential integration issues.”

The original starting point for the project, if the FIA had progressed the concept, was early 2019 and Gee admits that would have been a tight schedule. “From the outside, you could say F1 teams make theirs in six to nine months, but they are only producing two of them and are relying on a very diverse supply chain.”

It would have required a considerable investment in new capabilities for Ricardo, as Sundler explains. “We were going to set up a dedicated manufacturing facility for this. But even then, the load on that facility in the first six months would have been considerable.”

Ultimately, the FIA, under pressure from teams, opted not to pursue a standard transmission, stating at the time: “The council’s decision was based on consideration of both technical and financial information made available by teams and suppliers. The technical data provided revealed that gearbox technology in Formula 1 has largely converged and that, as a result, there is little performance differentiation at present. It was also noted that, due to the complexity of the components, gearboxes remain a sensitive matter in terms of reliability, and this was factored into the evaluations of the FIA technical department.”