BMW has detailed the forced induction tech, developed over 50 years, that has led to its 2019 2-liter 600ps DTM powerplant. Tech that could make its way into the next generation of ICE passenger vehicles.

In 1969, BMW won the European Touring Car Championship with the BMW 2002 TI, carrying out pioneering work and writing history in the process. The first BMW Turbo in motor racing – the M121 – provided the necessary drive.

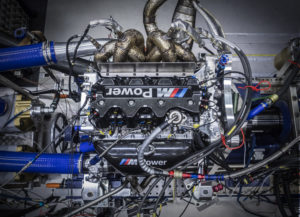

After many more BMW Turbo engines in the 50 years since then, the newly-developed BMW P48 engine will make its debut in the BMW M4 DTM when this season’s DTM kicks off at Hockenheim. Times may have changed, but the outstanding properties of the engine have remained the same.

Despite the 50 years that lie between them, the two high-performance engines have a number of similarities: both are straight, four-cylinder engines with a 2-liter capacity and a turbocharger. In both the BMW M121 and the P48, the sensitive engine components must be protected by a heat shield from the heat emitted by the turbo charger. A mechanical injection pump supplies the engine with fuel in both cases.

The pressure with which the combustion air is supplied to the engine can hardly be compared any more. With 0.98 bar of pressure, the first generation of turbo race engines achieved approximately 280ps at 6,500rpm. The exhaust fan was theoretically capable of developing a boost pressure of 1.76 bar. However, the pressure in the cylinder would have been so great, that the cylinder head would have lifted off.

Nowadays, boost pressures of up to 2.5 bar are possible with more than 600ps. This is made possible thanks to a crankcase and cylinder head that were manufactured in a special sand-casting procedure in the BMW Landshut foundry in Germany.

In the last 50 years, components such as the ignition distributor, fan, wet sump and boost valve have disappeared. There is no longer a direct charge air pipe, which supplies the engine with compressed air without any cooling. Instead, the P48 has a sophisticated dry sump system. The oil required for lubrication purposes within the engine is extracted immediately without any oil being lost through splashes. Another part of this system is the oil tank, which is directly attached to the engine. Efficient charge air cooling also allows for increased performance and efficiency.

©Martin Hangen/hangenfoto

Auxiliary units, like the starter and generator, are no longer a part of the engine, but are mounted on the transaxle gearbox behind the engine. Carbon-fiber-reinforced plastic has replaced the old aluminum weld-and-cast construction on the plenum chamber.

Furthermore, the butterfly is now moved electrically and no longer by a mechanical throttle rod. Instead of an open ignition harness, the electrical wires in the P48 are housed in a protective, carbon cable tray.

One of the key aspects of the P48 is its consumption. Compared to its predecessor, which itself was very efficient, the current engine has been made almost 10% more efficient. It is actually more than 50% more efficient than the M121 from 1969. This was achieved with the help of the high-pressure direct fuel injection, as found in BMW production engines, as well as a mixture preparation and combustion which allows the engine to operate in a ‘lean burn mode’.

A consistent minimization of friction losses, such as through the aforementioned oil system and the use of high temperature-resistant components that do not require cooling by the fuel, make the P48 one of the most efficient BMW race engines of this day and age. And despite the significant increase in power of about 100ps, the unit is designed for reliability and durability.

The turbocharger in the P48 supplies the engine with 400 liters of air per second. The pistons accelerate from zero to 100km/h in less than a thousandth of a second. The water pump shifts roughly 18,000 liters per hour, while 1,005 drawings were made for the final assembly of the engine, which consists of roughly 2,000 individual parts.

A new era in touring car racing is dawning with the BMW P48 and the Class 1 regulations – just as it did with the engine’s forefather from 1969. But how long is it before we see this BMW tech in a passenger vehicle?