The path is far from clear. The racing business is on the up but cost control is always at the forefront – from F1 to regional series – which means unfettered technology development is something of a rarity. It therefore falls to regulators to ensure rules allow development where it is beneficial and, most importantly, relevant, while reining in the excesses that lead to boom-and-bust cycles for series.

With these constraints in mind, APTI speaks to various engineers involved in powertrain development to gather their opinions on how the next decade may pan out. Unsurprisingly, their views coalesce in some areas and differed in others. But three main directions are clear: increasing electrification is a given, the potential for hydrogen is promising, and ICE will be around for the foreseeable future, coupled with either sustainable fuels or hydrogen.

However, Bruce Wood, MD of powertrain at Cosworth, is keen to point out that the direction will not be set from within racing: “We’ve definitely come to realize that motorsport is rightly the domain of the car manufacturers. So we will have little part, I believe, in driving the direction because that will come from the car manufacturers.”

Hywel Thomas, managing director at Mercedes AMG HPP, backed up this thinking. “I think the important thing is that we make sure that the direction we go in is one that manufacturers want to invest in. You want sponsors to invest. Somehow you have to keep a weather eye on how those different markets are going, and where the winners and losers are,” he says.

Electrification

Electrification of vehicles is here to stay, with manufacturers across the globe investing billions in development. Thus, it is inevitable that if motorsport is to be used as a marketing or development tool, BEVs must play a role.

Formula E is still the highest-profile pure EV series and has the greatest level of involvement from manufacturers, many of which certainly use it as a proving ground for control strategy development, if not direct component innovation. On this front, the series has fulfilled its remit well; being effectively an energy-efficiency competition makes it exceptionally relevant to the current path of road-car development. Whether it has proved as successful as a marketing tool is questionable, and it has failed to make the impact of some other FIA world championships. However, as it moves toward ever faster cars and longer race durations, the spectacle should improve and, with it, fan engagement.

The past few years have been less kind to other BEV series startups. Despite seemingly having an excellent package, ETCR has folded and others such as Extreme E are struggling to gain momentum. The World RX championship, with its electrified RX1e and RX2e classes, has proved popular with fans and competitors, but with its top-class cars currently (as of the start of September) sidelined following a calamitous battery fire during the UK round at Lydden Hill in July this year, it could lose the goodwill it has built.

However, there are positive developments. The Swedish Touring Car Championship is about to go all-electric. Always a hotbed of competition, touring cars globally have suffered from a dearth of high-level manufacturer interest in recent years but should be the ideal win-on-Sunday, sell-on-Monday model for EV manufacturers.

Despite this mixed outlook, the consensus is that although many series will likely go BEV over the next decade, it will be a long time, if ever, before they usurp ICE. As Arnaud Martin, chief officer of inverter systems and motorsport at Helix, suggests, “When you look at non-endurance racing, below one-hour races, I think there is big potential for electrification.” However, he believes that unless there is a seismic jump in battery technology, enabling greater power and energy density, this is the limit for the foreseeable future.

There is potential for swappable battery packs, although those championing their use in road cars are thin on the ground. In fact, Nio is the only manufacturer to bring them to market at scale, with the company’s EP9 hypercar concept – which Martin helped to develop – featuring swappable packs. However, there has, to this author’s knowledge, been only one attempt to run swappable batteries in racing: by the EVSR outfit at the 2021 25 hours of Thunderhill.

Others have expressed an interest, including Lotus with its E-R9 concept car (slated for a 2030 debut). Honda, via HPD in the USA, recently unveiled its eGX kart concept equipped with Honda’s MPP swappable batteries (which are available as part of a Battery as a Service offering in some markets). Despite the evident potential of battery swapping for endurance events, there seems to be little movement on the topic, with the FIA’s proposed ESV (electric sports vehicle) rules not specifically including the technology. However, as the rules are intended for modified roadgoing EVs, this theoretically opens the door for a swap-capable EV to compete.

It would seem, therefore, that EV races lasting more than an hour will not be feasible in the next decade. Fortunately, this still leaves plenty of scope for opportunity, and the arrival of several ‘entry-level’ series into the BEV racing space, such as Formula Foundation in the UK and the ACE championship (intended to be a feeder to Formula E), attests to the technology’s draw.

Martin is clear that in terms of motors and inverters, potent electric powertrains are now cost competitive with ICE. Many of the units that Helix deploys in single-make series are closely related to high-end road car units. “This is because they are cost-effective, they are reliable, they can achieve the performance. So as a result, they are a great choice for single-make series where nobody’s gaining an advantage from having a very lightweight, expensive powertrain. Our technology toward the high end of the automotive market actually has a really good match to single-make series.”

Batteries are a different matter. Their cost is and will remain a hurdle for the wider adoption of BEVs in lower formulae, particularly if the goal is performance parity with ICE equipment. The reason rallycross has been able to implement full EV at a high power level is the brevity of its races. A single charge at the start of the day, with a small battery pack, is sufficient to complete a day’s racing.

Though the cost of building new cars is not trivial, Kenneth Hansen, founder of Hansen Motorsport (multiple World RX champions and RX1e competitors), notes, “The cars are not very expensive to run as long as they are reliable.” Furthermore, the supply models with Kreisel, which brings backup parts to each race, means teams do not need extensive powertrain spares. “If we have a problem, we can go and buy it, rather than have to keep it in stock,” Hansen adds. The total powertrain cost for a four-year program for a single car is around €400,000 (US$430,000), which is comparable to the previous ICE cars. But what of hydrogen?

Lighter than air

Hydrogen is a divisive subject for those looking to decarbonize transportation, although it is more widely accepted as a solution in racing. To some, it is the silver bullet of sustainability, to others an inefficient use of sparse green energy as part of a cynical plot by oil and gas companies to keep themselves relevant. The truth is probably somewhere in-between; H2 can overcome some of the limitations of battery-driven propulsion but has its share of downsides too.

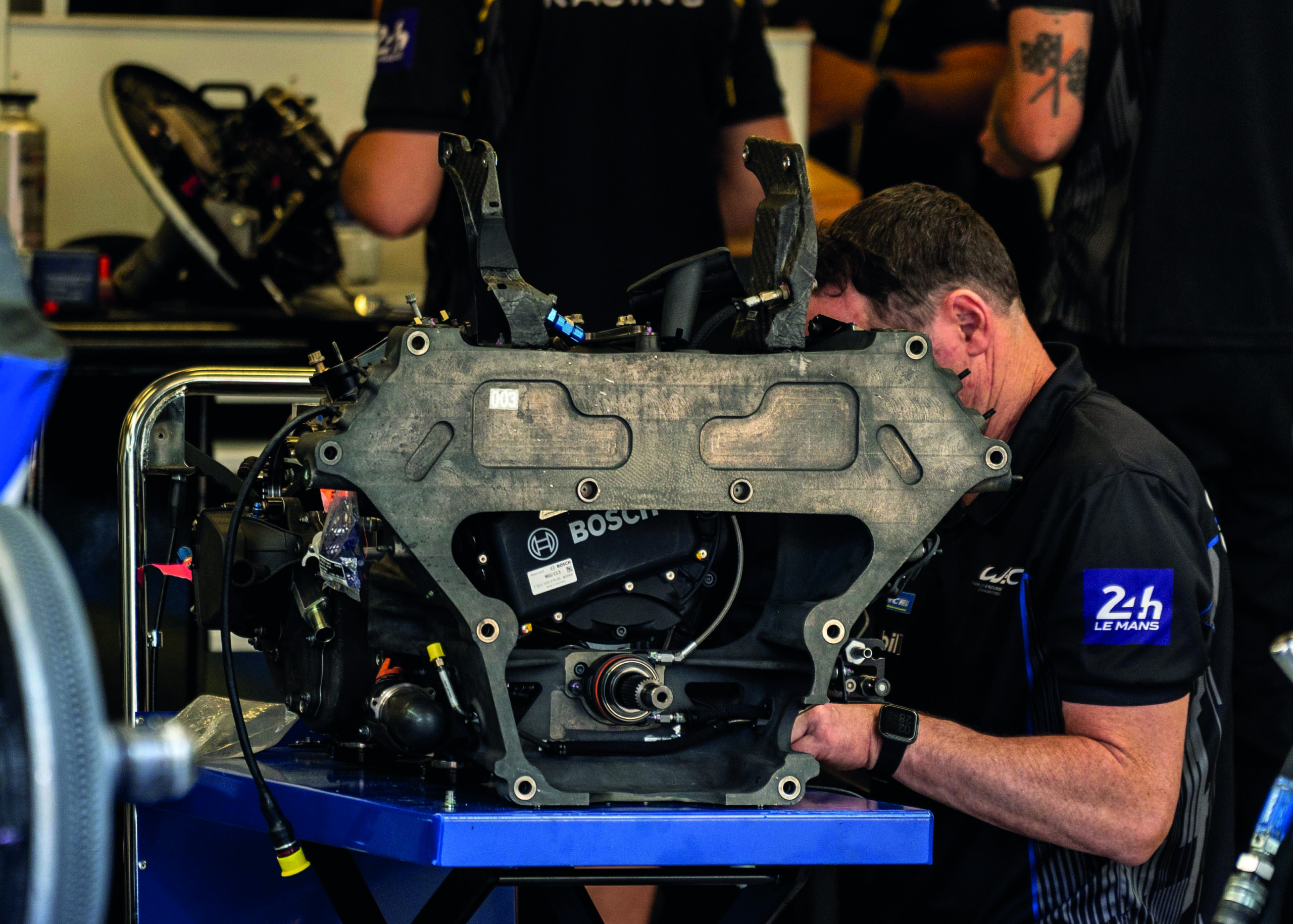

Out in the real world, some automotive OEMs are wholeheartedly backing the use of hydrogen in certain roles, while others dismiss it out of hand. In racing, its application is certainly promising, with several series looking to roll out hydrogen classes over the next couple of years. These include Extreme E, which recently announced a class from 2025; Dakar, which already has provision for H2 racers; and, most notably, Le Mans, from 2026. Following a rule tweak announced in 2023, both fuel cell and H2-fueled ICE will be permitted at Le Mans.

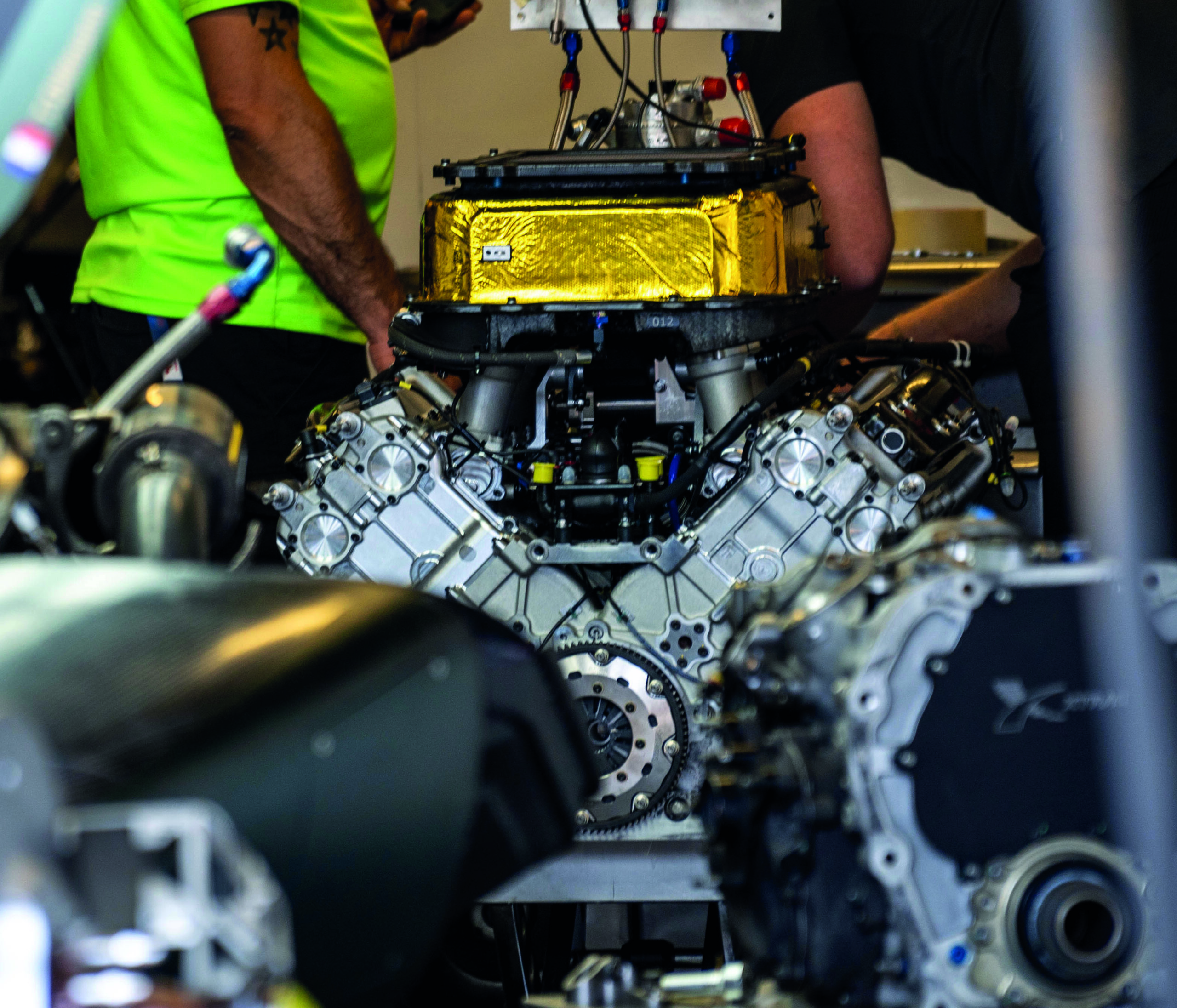

The use of H2 in ICE could provide a quick route to tailpipe emissions-free racing over long distances. Converting existing ICE engines to run on hydrogen is a (relatively) straightforward process, with several manufacturers working on development of dedicated injectors. There are, of course, new approaches to combustion systems to be unraveled to gain parity with gasoline ICE, but the mechanical basics of engine design remain the same.

Fuel cells should not be ignored, because they represent a more effective use of H2 than even the most efficient ICE, as the efforts of Swiss outfit Green GT in preparing proof of concepts for the ACO-led Mission 24 have shown. Plenty of work is currently underway in the wider transportation sector, creating higher-power fuel cells coupled with miniaturized ancillaries and high-power-density buffer battery systems, all of which can be applied in racing given the right support.

Martin believes that FCEV-powered racers would be the ultimate solution for zero-emissions racing beyond sprints: “I’d like hydrogen and fuel cells to develop further than they are now, because I like the ability to refuel reasonably quickly. I think if you can reduce them in size, which is slightly against fuel cell at the moment, that’s a reasonable alternative to where we are now. A pure electric drive car, doing a 24-hour race and winning is what I’d like to see happen. Because at that point, it’s a really good marker that electric technology

is a true alternative to ICE.”

Again though, although the power element of the powertrain is reaching viability – whether H2 ICE or FC – energy storage remains challenging. The volumetric needs of hydrogen are its biggest drawback.

The GCK Forvia shown at Le Mans had an 8kg hydrogen capacity sufficient for between 25 and 40 minutes of running (at a maximum ICE output of 450kW). However, the tank takes up far more space than a traditional gasoline fuel cell. Toyota’s H2-converted ICE Corolla has also had a degree of success in the Super Taikyu series, and the company is currently refining its liquid hydrogen fuel system.

Liquid H2 has superior energy density, allowing for smaller tanks, but has its own set of challenges, notably the requirement to store it at -253°C. The refueling time for the Corolla is now almost comparable to a regular gasoline ICE, but issues such as fuel pump durability (due to the very low temperature and lack of lubrication) still need to be addressed. Although these projects are undoubtedly pushing the envelope of H2 in racing, they are still well wide of the performance mark if the goal is achieving something like LMH capabilities.

It is for this reason that the opinion of Fred Barozier, general manager at Pipo Moteurs, differs from Martin’s. He feels the idea of an H2-fueled car winning Le Mans anytime soon is far-fetched. “For me, it will not happen because no cars are ready to fight with the current hypercar with hydrogen. Maybe they will have to do some kind of specific formula, like it was with Formula E, and just fight between engine and fuel cell, for example, but not really fight between hydrogen cars and biofuel cars. Otherwise, you have to put 500kg more on the biofuel cars just to have some balance of performance.”

ICE future

Every engineer consulted for this feature, whether they specialize in BEV or combustion propulsion, is of the same opinion: gasoline ICE is not going anywhere soon because competing technologies are simply not mature enough to match its bang for buck, yet. However, the ever-greater use of sustainable fuels, either biofuel or synthetic, will provide the environmental credibility needed.

At the very top of the pyramid, F1 is set to retain an ICE element for the foreseeable future, albeit with a greater degree of electrification. The new powertrain rules coming in 2026 will be in play well into the next decade and should push understanding of lean combustion to even greater heights, with the associated benefits to road car programs. At a regional and national level, ICE is the only viable option for many. Looking at the rally pyramid, for example, the thousands of Rally2, 3 and 4 machines are not going to suddenly turn EV.

For those looking to burnish their green credentials, hybrids can step into the breach and provide a degree of electrification without the full cost of going BEV. At a top level, LMDh has proved that spec hybrids can be attractive to manufacturers. In fact, John Manchester, operations director at Gibson Technology, feels they represent a better solution than pure EV in the majority of cases: “I think the hybrid is a far better solution than a pure EV and has proved it [at Le Mans and in F1]; they’ve been doing that for a long time. I believe that is the better option and long term the future is having an ICE hybrid system running on sustainable fuel.”

Moving down the racing ladder, efforts such as the BTCC’s successful adoption of a spec hybrid system plots a potential path for national series. However, even mild systems come with associated costs and Manchester wonders whether – in some classes such as LMP2, where Gibson is heavily involved – there is a need for them. The current engine rules are cost-effective, the class is popular and there is no OEM involvement lobbying for marketing-based gestures – the argument being, if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it.

And there we have it. The motorsport powertrain landscape a decade down the line will likely feature much of what we see now, albeit in different proportions. BEV will certainly have a more prominent role, but ICE will still be around in one form or another. Hydrogen will also likely have its place, although this will hinge on how quickly the wider global hydrogen economy gets up to speed.

There will be opportunities to be seized and mistakes to be made, but there should still be plenty of scope for engineering excellence to shine through.