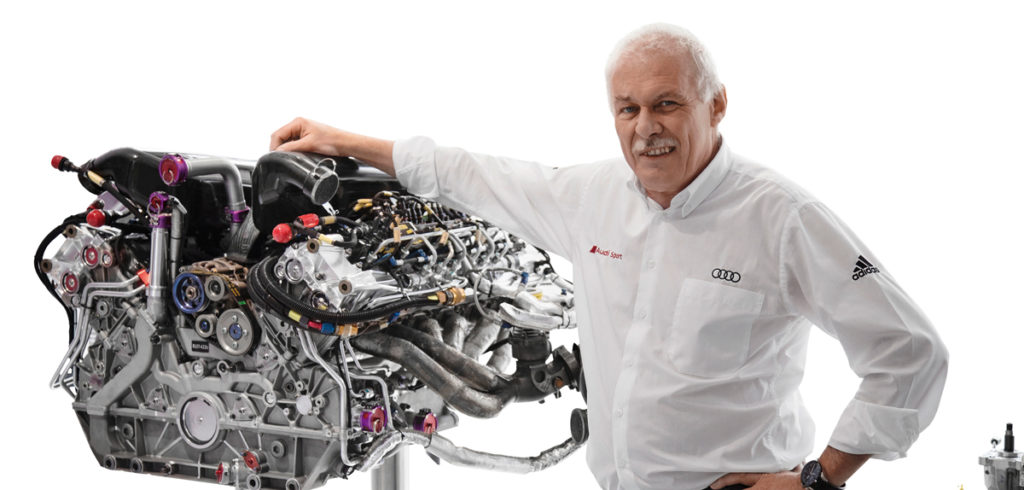

The start of June saw Ulrich Baretzky, long time head of Audi Sport’s engine department, retire. Architect of many of Audi’s motorsport successes over the past three decades, Baretzky started his engineering career with BMW Motorsport, joining the company as a graduate in 1982.

He didn’t set out to be a motorsport engine designer. In fact, his initial aim was architecture, but he shifted his studies to mechanical engineering. An interview with BMW’s Paul Rosche, suggested by a friend who already worked at the company, saw him start out on a path that would eventually lead him to design winning engines in Trans Am, IMSA, DTM, Super Touring and of course, endurance racing.

Notably, Baretzky has had a long association with turbocharging. Shortly after joining BWM he was involved in its turbocharged Formula One engine project and when he moved to Audi in the mid-1980s, he worked on the development of its five-cylinder, turbocharged engines for Trans Am and IMSA.

The 1990s saw his focus switch to naturally aspirated motors in DTM and then Super Touring, but when Audi decided to return to Le Mans at the end of the decade, Baretzky’s choice of powerplant for the multiple Le Mans-winning R8 was a turbo V8.

The R8 engine pushed the boundaries of innovation with its use of gasoline direct injection from 2001, but it would be his pioneering work with diesel that sealed Baretzky’s legacy. Recalling when he first suggested to the Audi board that the team should take advantage of new rules at Le Mans that allowed diesels, Baretzky said, “I went to them and told them I think we should run a diesel at Le Mans. They looked at me and told me, ‘You’re a good man, but you should not drink so much!’”

Ultimately, he would prevail, and Audi’s diesels, the R10, R15 and finally R18, would go on to secure eight Le Mans victories. Though still convinced diesel has a valid place in endurance racing, he admits he was less enamored with the arrival of hybrids.

Audi started out with a mechanical flywheel hybrid system on the R18, which Baretzky noted, “is actually an environmentally friendly system. It is complicated, but not like an electric system, but is limited on performance. At 2MJ it is OK but beyond that it is not, so we switched to the electric with all of the problems that brought”.

He continued, “I used to illustrate it like this. I’d put a little glass of water on the table, maybe 3cm of water, and point out this is the amount of fuel that has the same energy as the complete hybrid system. It’s ridiculous. 8MJ was the most powerful system, whereas one liter of fuel has around 40MJ. But you are carrying along all of the complicated system as well.”

Currently, his personal opinion is that hydrogen combustion is a valid route forward for sustainable powertrains, both in motorsport and general automotive. Of course, this does not fit with the ACO and FIA’s ideas for hydrogen at Le Mans, which are purely fuel cell based. “With a fuel cell, they are heavy and massive and the power is quite limited,” he remarked. “We (Audi) made studies comparing fuel cells and combustion engines. The efficiency from a fuel cell at high power is not there, they are only good at low power, but then you need a huge fuel cell. We developed a concept that overcomes that with a hydrogen combustion engine.”

However, he is happy to admit he is done battling established ideas. “My time is over and I have done so many things in my professional life. If someone told me I would do them, I would