Motorsport needs to be proactive in presenting to the public the engineering innovations and efficiency gains it has made – and continues to make.

A raft of new powertrain regulations are set to come into force in 2026. F1 will gain new engine regs, the WRC as well, while at Le Mans the long-mooted hydrogen class should hit the track. All of these present a great opportunity for motor racing to keep itself relevant to the general public and, as a consequence, to the manufacturers that stump up cash to compete at the highest level. But based on its track record of the last 10 years, it needs to be proactive to get this message across.

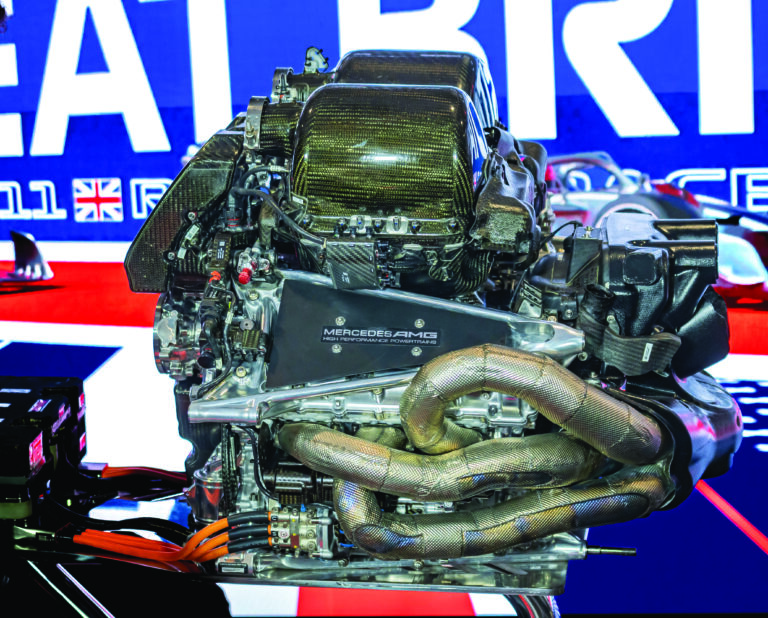

F1 is a prime case in point. The 2014 rule changes led to the development of the most efficient combustion engines to date – an incredibly impressive achievement. Unfortunately, F1 and the FIA did a terrible job of telling the world. Here was a development path in perfect tune with the direction OEMs were taking, but rather than capitalize on this, the FIA was muted in its trumpeting and the manufacturers clammed up. Secrecy was the name of the game, and it is only really now, a decade later, that teams are talking openly about the innovations they perfected. Mercedes AMG HPP’s Hywel Thomas reflects that this was a missed opportunity to show just how relevant motorsport could be.

Taking the MGU-H – soon to be consigned to the history books – as an example, he says, “Everyone thinks that is the work of the devil, but actually it’s a fantastic engineering tool; we probably didn’t talk about it enough.” Mercedes is now deploying electrically driven turbochargers on its road cars. The same reluctance to trumpet these innovations could also be said for the incredible advances in combustion science that 2014 ushered in. Never had engine efficiency been subject to such intense scrutiny. While it would be easy to dismiss the efforts of racing, it shouldn’t be forgotten that for more than a decade, well over 1,000 engineers have dedicated their lives to eking out every last ounce of performance from 100kg of fuel. If you had told a development engineer at a major manufacturer in 2010 that a hybrid ICE would be hitting over 50% thermal efficiency 10 years down the line, they would have laughed at you.

“If you look at what was achieved in 2014 with the pre-chamber combustion, that was just an awful lot of efficiency,” recalls Thomas. “And, again, not something we talk about a huge amount. You think back to it and maybe these are the sorts of mistakes we made, because you are seeing those systems in road cars now. The 2014 regulations were seen a bit as the spawn of the devil, but look at what has actually come from them.” Teams will face the same conundrum in 2026. The new rules will see combustion technology pushed even further, with significant reductions in allowable fuel energy and the removal of a vital tool in the MGU-H. And of course there are the challenges presented by the electrified portion of the power units.

As Thomas highlights, it is not an easy balance to strike. In the case of Mercedes, the company has probably invested billions in power unit development and doesn’t want to see any advantages squandered. “It’s a very difficult part of the competition. You don’t want to lay out what you’re actually doing. But you look back and you think, crikey, we have some real innovations. And we’re in that same position with 2026 and the combustion, where we need to make those sorts of steps, that kind of innovation, that kind of work, because it’s a big challenge.”

With the extra limitations in place – not only the loss of the MGU-H but a ban on in-cylinder pressure sensing, compression ratio limits, not to mention budget caps – the developments made will be, if anything, even more relevant to mainstream automotive. 2026 is an opportunity that shouldn’t be squandered. In a world where every endeavor is set against the backdrop of emissions reduction, the sport of motor racing would do well to trumpet its not insubstantial achievements.